Faith Nyasuguta

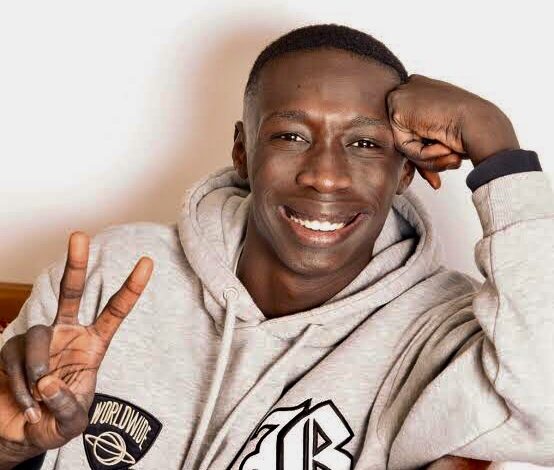

With over 146.6 million followers, Khaby Lame recently surpassed Charli D’Amelio to become the most followed TikToker thanks to his distinctly West African brand of comedy, the kind that doesn’t suffer fools gladly and is steeped in sarcasm.

The 22-year-old Senegalese-born creator simplifies the already simple in his TikToks, where he silently mocks elaborate “life hacks” while looking straight at the camera with eyes widened and giving a big shrug to punctuate his point.

As writer Chris Stokel-Walker put it: “It’s that opposition to what D’Amelio is and represents – white, middle-class, already-rich America – that makes Lame so intriguing to audiences.”

Separately, Kenyan creator Elsa Majimbo’s content is laced with a more jovial brand of comedy. The chess player turned comedian became a star on Instagram during the pandemic for her skits featuring potato chips, a pair of sunglasses, and her signature laugh.

It’s a fact, African creators have been responsible for some major viral moments, such as Nimco Happy’s viral hit and the “Don’t Leave Me” challenge created by comedian Josh2Funny.

Additionally, the Ikorodu Bois routinely rack up numbers for their innovative remakes of films and TV shows. A world of incredible content creators exists outside of what your feed may typically serve up, and they’re having to push much harder for a global audience.

For Nigerian creators like Charity Ekezie, who has 1.2 million followers on TikTok, Lame’s rise to the top serves as evidence that global fame is attainable — but only for a handful in the current creator climate.

“When people talk about influencers, I don’t believe African creators are mentioned at all, except for Khaby and maybe Elsa,” the 30-year-old, who has been creating content since 2014 says.

A search for her name on a major influencer database would turn up no results despite her huge following as is the case with many African influencers.

“We’re not positioned anywhere, except for the very few who work twice as hard to break out and it takes a lot,” she said. “That’s why we’re celebrating Khaby.”

According to a report in Tech Cabal, one of the major hurdles facing African content creators from tapping into the $100 billion global creator economy is that many are still shut out from the incentive programs that some platforms offer despite having huge audiences and the numbers to back them up.

For instance, Snapchat Spotlight, where users get paid for their snaps, is only available in select countries, excluding most of Africa.

Substack, which uses Stripe for paid subscriptions, is currently not supported on the continent, and the TikTok creator fund is only available to creators in the US, UK, Germany, Italy, France, and Spain.

This means creators like Angella Summer Namubiru in Uganda, whose content has earned her 5.4 million followers, are unable to access the pool of money assigned for keeping the platform propped up with content.

Still, creators like Ekezie keep trying. Like many people, downtime during the pandemic led Ekezie to join TikTok in 2020, where she tried her hand at everything from creating dance videos to DIY tips.

But it’s her skits where she dunks on ignorant ideas about what life in Africa looks like that have made her widely popular.

Ekezie, who was raised in Cameroon, describes her content as “sarcasm and subtle education.”

When a user questioned how Africans had access to the internet and TikTok, Ekezie responded with a skit claiming that families were visited weekly by a community chief priest who performed a ritual of incantations to generate internet.

“My whole point was just to pass the message without actually passing the message,” she said, jokingly. “The more I made videos, the more the questions came.”

Her largest audience is in the US, followed by the UK, but even with more than 1 million followers, Ekezie says she is yet to get the level of brand engagement or opportunities that a creator based in those respective countries would be eligible for. Regardless, she remains optimistic that it is simply a matter of time.

The challenges faced in creating content, growing audiences, and being able to leverage this for monetary gain mirror US debates over who gets to be an influencer, which has historically fallen along racial lines.

Even with the number one spot on TikTok, Lame is nowhere to be found on Forbes’ illustrious TikTok rich list, but I imagine this will change in the next 12 months. The TikToker signed a multiyear deal with Hugo Boss and was recently named as a global Binance brand ambassador.

Lame’s success is the stuff any young, aspiring African influencer dreams of,

Lame was a factory worker in Italy when he started producing content. African content creators are pushing through by any means necessary to create media for global audiences, whether it means waiting extra long for a YouTube video to upload because the service in the area is limited or planning around the rainy season to shoot outside.

For some, influencing and content creation are vehicles to escape underemployment and the lack of opportunities.

Mostly when the globe refers to Gen Z, influencer culture and content creation, but exclude Africa, it falls short of presenting the full picture.