Avellon Williams

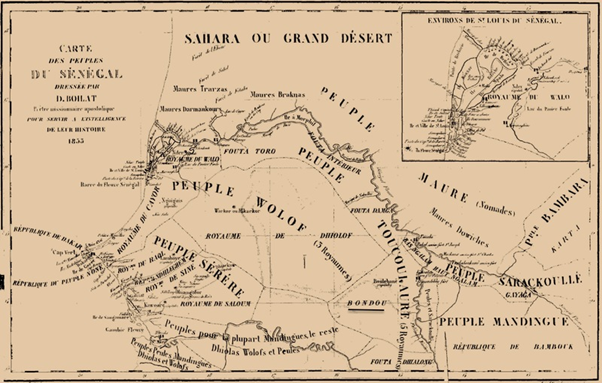

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO- The famous man Ayuba Suleiman Diallo was also known as (Job Ben Solomon) to his fellow Europeans born in 1701 in the nation of Futa Toro (now name Senegal) into a wealthy noble Fula tribe whose father was one of the most prominent Muslim families in Senegal in the Eastern region of Africa.

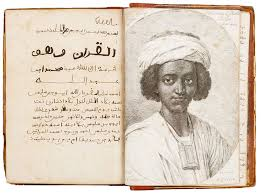

As a Muslim who survived the Atlantic slave trade and enslavement in colonial America, Diallo is best known for his memoirs.

A young merchant by 1729, Diallo grew up in a relatively privileged environment. The same year he and his interpreter, Loumein, were captured by Mandinka slave traders who sold him to the Royal African Company, the largest English slave enterprise in the region. In turn, the company sold him to a sea captain, who brought him to Annapolis, Maryland, where he began his life as an enslaved person in the British colonies.

The first job Diallo had was to work in the tobacco fields, but since he was not used to working hard, he was quickly transferred to herding cattle. Due to the cruel treatment of slaves practicing their African faiths, Diallo kept his faith hidden until he was discovered by white children praying to Allah in the woods who mocked him and pelt him with rocks.

After being publicly humiliated because he continued to practice his faith, Diallo fled his owner in 1731 but was eventually captured and imprisoned in the Kent County, Maryland, courthouse.

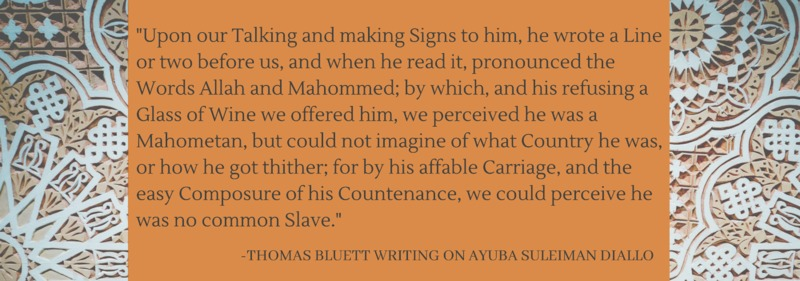

During his incarceration, he met Rev. Thomas Bluett, an attorney, judge, and missionary who was delightfully surprised by Diallo’s ability to read and write in Arabic. He was also fluent in the Wolof language, which he translated for Bluett. Despite Bluett returning Diallo to his owner, he did help Diallo convince the owner of his noble origins.

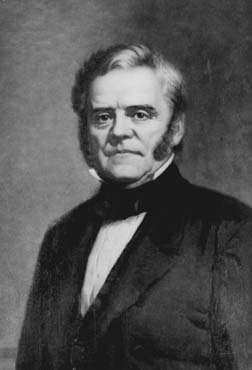

Diallo penned a letter in Arabic intended for his father in FutaToro, asking for his father’s assistance to help him return home. Bluett attempted to deliver the letter to Bondu, however, the letter changed hands several times among British officials and still failed to cross the Atlantic, finally finding its way into the hands of James Oglethorpe, the British aristocrat who founded the Georgia colony in 1732. Oglethorpe also held a position with the Royal African Company, which controlled the British slave trade.

Oglethorpe bought Diallo, freed him, and sent him to London to start a new life. The young Diallo found himself mingling with the social elite of London.

As a result of Diallo’s connections to West Africa, British colonists working for the Royal African Company hoped to build stronger relationships for trade in the Senegambia region, particularly for ivory, gum, and gold. Despite this, Diallo was highly trained in theology and not trade, and as a result, proved ineffective in fulfilling the economic goals of the Royal Africa Company.

Even with those contacts, he was still targeted by slave catchers who hoped to capture him and sell him elsewhere. He contacted Bluett, fortunately, who was in London at the time. Bluett, concerned about Diallo’s safety, raised funds among the elite in London, including the Duke and Duchess of Montague, members of the royal family so that he might return to FutaToro.

Diallo in exchange consented to Bluett’s writing of his memoirs, which were completed only a year after Diallo arrived in West Africa, Memoirs of the Life of Job in 1734.

Bluett stated that Diallo “was no common slave,” and furthermore, he could not be considered both a common West African or a common Muslim. It was his elite status that enabled him to escape slavery, a privilege most West Africans, regardless of whether they were Muslims or not, did not possess. It is revealing, however, as his experiences show that some Europeans in colonial America were attracted to the education and religious devotion of Muslims. As soon as the British colonists encountered Diallo, a Muslim of noble lineage and exceptional education, they both assisted in his freedom and accommodated his Islamic practices.”

In 1734, Diallo returned to Bondu to discover his father had passed away, and his wives had remarried. His children, however, were still alive. In an ironic twist of fate, he worked as an interpreter and slave trader for the Royal African Company until he died in 1773.

Diallo’s memories published by Bluett constitute one of the earliest slave narratives to gain popularity with the British and American abolitionists during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Diallo’s story remains a vital part of understanding the Atlantic slave trade.