Avellon Williams

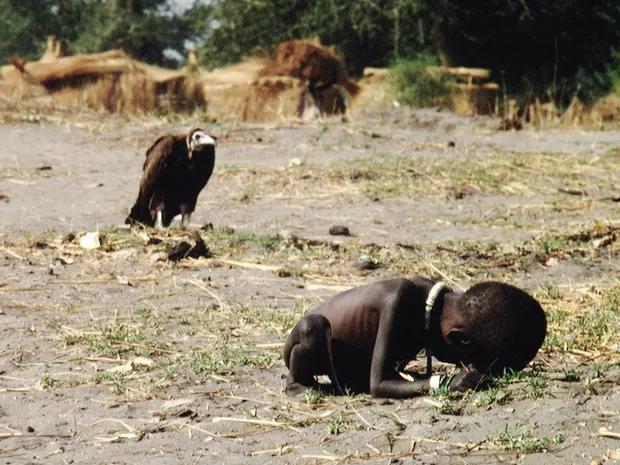

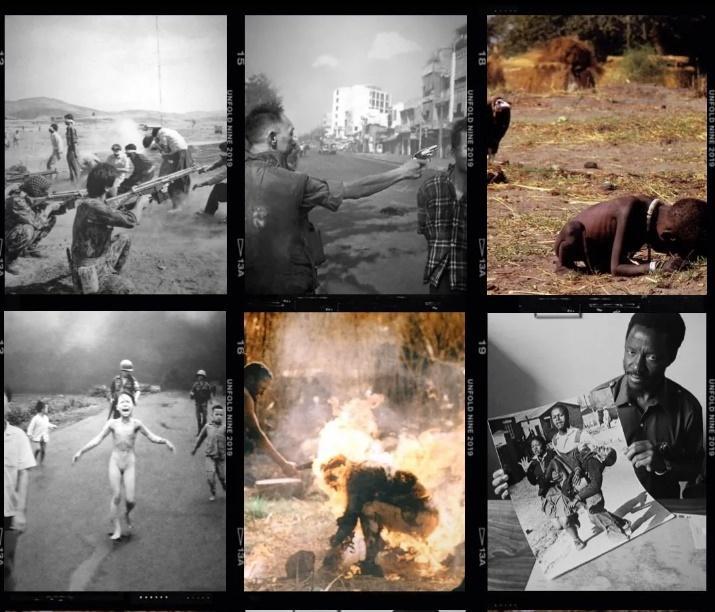

JOHANNESBURG- The picture above shows a vulture and a starving child and is a landmark piece of photography by Kevin Carter. During the Sudanese famine in 1993, the photograph became known as “The Struggling Girl.”

Because Britain decided to slow down Sudan’s industrialization efforts during its early colonial years, Sudan has always had an enormous budget deficit and national debt.

When the poor country was struggling to recover from its economic ruin and terrible debt, famine struck. As part of the United Nations assistance, food centers had already been established in the country, and lessons on crop growth and speeding up the economy had already been taught to the citizens.

Kevin Carter captured the image during a trip to Sudan to cover the civil war ravaging the country. His future success as a Pulitzer Prize winner was unknown to him at the time. Even less did he realize that he would succumb to depression soon after receiving the award.

In a confrontational photograph, Carter’s depicted Sudan’s biggest problem: poverty, in an uneasy light. A young, starving child (believed to be a girl) was attempting to crawl toward a United Nations feeding center about half-mile away in Ayod, Sudan (now South Sudan). Although the piece is bold in its message, many subtle details make it powerful. A barren wasteland can be seen in the background without any signs of previous human activity; it appears like a place where little vegetation grew or where a disaster occurred.

It was probably caused by the harsh sun that causes droughts in Sudan for many years at a time. The main object in the photograph – the child – is being stalked by a vulture a little closer to the viewer. Due to the protrusion of the child’s rib cage from her chest, the starving child appears paralyzed by hunger.

As reported, Carter sat beneath a tree, prayed to God, and cried after taking those photos in Sudan. “He was depressed afterward,” Joao Silva said, “and kept saying he wanted to hug his daughter.”

Upon returning to Johannesburg, Carter published this photograph in the 3 Pulitzer Prize Photography New York Times to emphasize the need to help the Sudanese. He sold his photograph to the New York Times, which ran it on March 26, 1993.

In the aftermath of the photo, the plight of Africa was brought to the attention of the world. People criticised Carter for not helping the girl, but they failed to realize that he was surrounded by armed soldiers on that day as reported, and as a result, they could not touch or interact with the famine victims.

The story of Kevin Carter illustrates the morbid history of violence and inhumanity that journalists witnessed and more so the tragedy occurring in Sudan. It shattered the complacency of people generally insulated from such struggles. There was a disturbing call to action to help those in other parts of the world who truly needed it.

Although winning the Pulitzer Prize put pressure on him, it did not directly cause his death as reported. Nonetheless, it contributed to the guilt and stress he had accumulated while documenting some of the worst places on earth.

As a result of his work, the Sudanese famine became internationally known. There is no doubt that Kevin Carter left a lasting impression on the world.

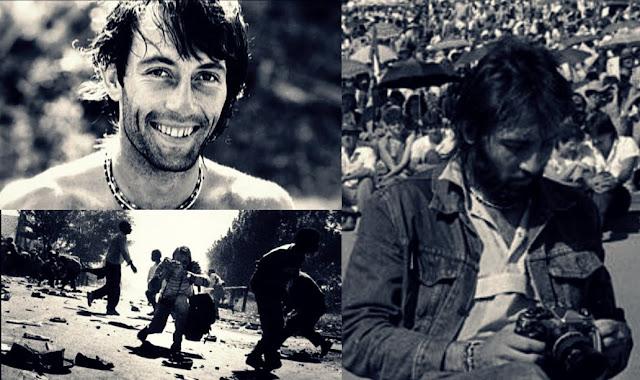

The Rise and Fall of Kevin Carter

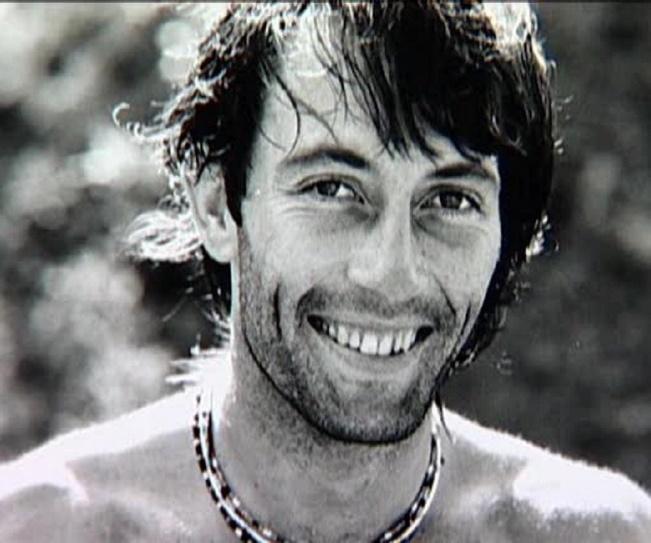

Born on September 13th, 1960, Kevin Carter was a South African photojournalist and member of the Bang-Bang Club. His photograph depicting the 1993 Sudan famine won him the Pulitzer Prize. As a result of reporting violence and death, and dealing with his own demons, Carter fell into a life of disorder and heavy drug use. The result of this was that Carter committed suicide at the age of 33.

Originally from Johannesburg, South Africa, Carter grew up in a middle-class family and lived in a neighborhood dominated by whites. During his childhood, he witnessed police brutality towards blacks living illegally in that area. As a result, he wasn’t pleased with what he saw and neither was he pleased with his Catholic parents, who considered themselves ‘liberals’ and did nothing about the issue.

As Carter abandoned his plans to become a pharmacist, he was forced to join the South African Defense Force (S.A.D.F.), which was mandatory for all white males who finished school or turned sixteen (16), unless they were physically disabled.

Carter witnessed other servicemen insulting a black waiter in the S.A.D.F, and he stepped in to defend him. He was badly beaten by them and was called “Kaffir-boetie” (a nigger lover)an ethnic slur that is used in reference to black Africans in South Africa.

The incident led Carter to go on leave without pay so he could restart his life as an RJ (Radio Jockey) named David in Durban. Even though he desperately wanted to see his family, he was just too ashamed to go back. As a result of losing his job, Carter swallowed sleeping pills, painkillers, and rat poison in an attempt to commit suicide. He survived.

Following his recovery, he returned to the S.A.D.F to complete his service. On guard duty at the air force headquarters in Pretoria in 1983, a bomb attributed to the African National Congress (A.N.C) exploded, killing 19 people and injuring 217. In the aftermath of this attack, Carter decided to become a photojournalist.

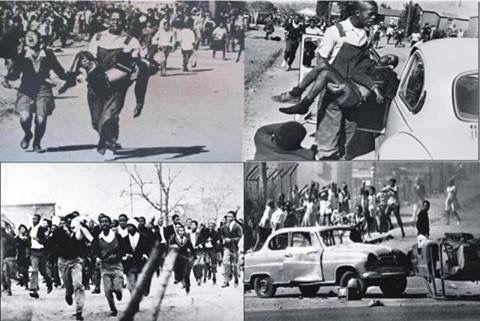

As soon as Carter completed his service, he got a job at a camera supply store and then started working as a sports photographer for the Johannesburg Sunday Express. Throughout South Africa, riots broke out in black communities in 1984. It was only through Johannesburg’s The Star that Carter was able to expose the brutality of apartheid to the world.

In the mid-80s, Carter was the first photographer to capture photographs of an execution known as necklacing. In this method, a rubber tire is filled with gasoline, diesel, or oil, then placed on an individual’s neck, which is then set ablaze to kill them. In most cases, the victims were beaten badly, hit with stones, stabbed, or shot before they were set ablaze. According to some reports, it took the unfortunate victim twenty minutes to die (if the victim wasn’t shot first).

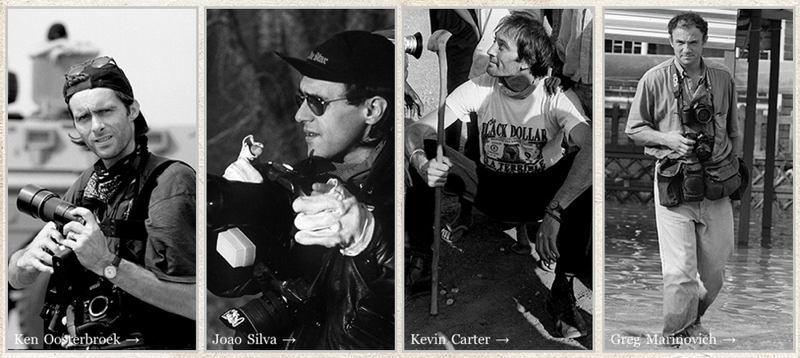

In 1990, Mandela’s A.N.C and the Zulu-backed Inkatha freedom party were engaged in a civil war. Working alone in the black townships was dangerous. To reduce danger, Carter had to team up with four friends, including Ken Oosterbroek, editor of the Star, Greg Marinovich, and João Silva. Their ability to capture the violence in the country earned them the nickname Bang-Bang Club by Living, a Johannesburg magazine. Symbolizing the gunfire and violence they are constantly exposed to.

In 1991, Greg Marinovich won a Pulitzer Prize for his photographs of an A.N.C. supporter stabbing to death a Zulu with a machete and burning him alive in September 1990. As a result, the stakes were raised for the rest of the team, especially Carter. As part of his mission to document famine-stricken Sudan (South Sudan), Carter and Joao Silva headed north in 1993.

A dark cloud began to loom over the young photographer. Through his drug addiction and alcohol abuse, he entered a great depression. While covering the first multi-racial election rally for Nelson Mandela, a crumbling quality of his work became evident, and he was seen staggering around the event.

Later that same day, he crashed into a suburban house and was jailed for ten hours on suspicion of drunken driving. At the time, he worked for Reuters, and his superior was very angry with him for retrieving the Mandela photos from the police station. A growing problem of his drug addiction had also affected his relationship with his girlfriend. During Easter, she told carter to leave until he cleaned up his act.

There were only two weeks left before the election, and Carter’s job was in jeopardy, his love life was in trouble, and he had nowhere to live. On April 12, 1994, Carter received a phone call from the New York Times informing him he had won the Pulitzer Prize. Carter preferred to ramble on about his personal life than explain why he had just won a Pulitzer Prize, according to the New York Times representative who spoke with him.

On April 18, the Bang-bang Club covered an outbreak of violence in Tokoza Township, ten miles from downtown Johannesburg. Carter returned to the city shortly before noon, with the sun too bright to take good photos. He later learned that his best friend Ken Oosterbroek had been killed in Tokoza and that Greg Marinovich was badly injured. In the aftermath of the loss, Carter returned to Tokoza as the violence escalated. A few days later he mentioned to some of his friends that it should have been him and not Ken that should have taken the bullet.

Carter was hired by a publication to photograph the French president’s visit to South Africa, but his photo was not received in time for publication. According to them, the photos were of poor quality and they wouldn’t have used them anyway. Times magazine assigned Carter to a Mozambique assignment on July 20, but Carter missed his flight despite setting three alarm clocks to wake him for an early morning flight. In addition, he forgot about the undeveloped film from his trip to Mozambique on the airplane when he returned six days later.

Upon reaching his friend’s house, he realized his mistake, but when he raced back to the airport to get the photos, he was unable to find them. After being distraught, Carter returned to his friend’s place and threatened to commit suicide.

On July 27, 1994, Oosterbroek’s widow was the last to see Carter alive. Carter turned up at her home unannounced as night fell to discuss his troubles, but the widow was unfit to offer advice after losing her husband three months earlier. Carter parked his red pickup truck around 9:00 pm at a field he used to visit often as a child. A silver gaffer tape was used to connect a garden hose to the exhaust pipe and run it to the passenger-side window. His knapsack served as a pillow as he waited for death after turning on the engine.

There was a suicide note left behind by Carter, which read as follows:

“I am really really sorry… the pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist… I am depressed…without phone money or rent… money for child support… money for debts… money!!!. I am haunted by vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain… of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners…” and he ends with this “I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”