Faith Nyasuguta

In a span of just two years, 89 Kenyans -with more than half of them being female domestic workers – have died in Saudi Arabia , the Kenyan foreign ministry says.

One of the victims, Alice Awor Tindo had only been working in Saudi Arabia for three months when friends and relatives back home in Kenya started receiving distressed calls and WhatsApp messages.

According to Reuters, the domestic worker ,30, revealed to them that her employer had impounded her passport and refused to pay her. Alice was prohibited from having a phone, so she hid her phone and sought to switch households.

“I am not in a good condition,” the single mother sent a message home in the Kikuyu language, dated June 9, 2020, as shown to Reuters by her family.

“I told my employer that I want to change jobs, but she told me that I will only leave this place when I am dead.”

Tindo’s body was found dead in her bedroom by her employer in Saudi’s Najran province four days later.

A report handed to her family by Saudi police had come to the conclusion that Alice died in her sleep and declared it a ‘normal death’. However, her father, John Awor Tindo disputes the information.

“Alice was a healthy young woman,” the 56-year-old farmer said standing by his daughter’s unmarked grave on a hillside cemetery near their home in the western Kenya town of Elburgon.

“It’s very mysterious. No one can just die in their sleep like that for no reason. There must be a cause. There should have been some follow-up.”

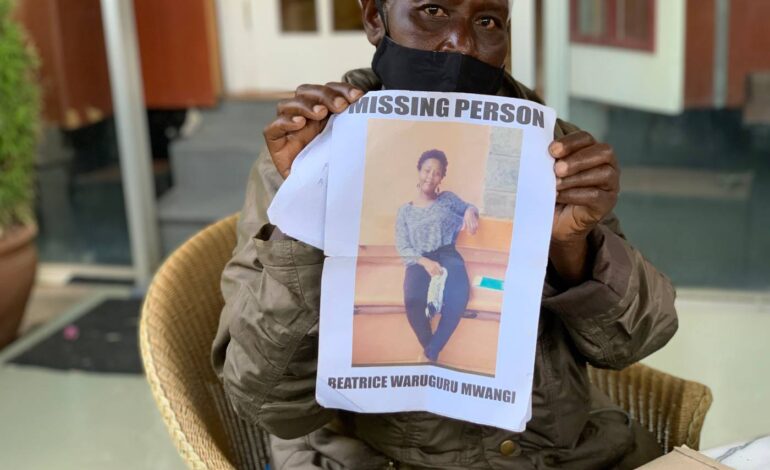

The Tindo family is just one of the increasingly bereaved Kenyan families sounding the alarm over the sudden deaths of many female relatives working in Saudi Arabia.

Kenya’s foreign minister notes that only three deaths were reported in 2019.

In most cases, the cause of death is given as cardiac arrest, natural death or suicide. However, many families remain unconvinced, and rights groups believe the deaths may be linked to a surge in abuse against domestic workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We believe they were killed,” Fredrick Gaya, a social activist, who has petitioned the Kenyan legislature on behalf of over 30 families and mistreated migrant workers.

“These women were suffering in the days before they died … they were being tortured by their employers. Some were burned with hot water or had dogs set on them. It’s not possible they all died of cardiac arrest or natural causes.”

The situation is also replicated in neighbouring Uganda where officials have raised an alarm on the deaths of its nationals in Saudi Arabia among other Gulf nations in recent months.

The embassy in Nairobi is yet to comment on the issue.

THEY RETURN AS CORPSES

According to Gaya, there are no autopsy results to confirm the causes of deaths when the bodies are repatriated, adding that Kenyan authorities should conduct post-mortems.

To add salt to injury, Gaya said the majority of the grieving families go through a hard patch in a bid to ferry the remains of their loved ones back home. Often, the process involves stressful months of painful bureaucracy and it costs thousands of dollars, he added.

Families have had to fundraise or take loans to settle the huge bills. Those unable to raise the funds have however, been pushed into leaving the remains of their loved ones in the hands of Saudi authorities.

Saudi Arabia depends on millions of low-paid foreign workers to execute domestic jobs from house maids, care-givers and nannies to drivers and security guards.

Three in every ten people currently residing in the oil-rich kingdom’s that boasts of a 35 million population, are migrants, majority from Asian and African countries.

However, for decades, Saudi Arabia – alongside other Gulf nations including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman – have faced criticism from rights groups for a sponsorship system that leaves migrant workers exposed to abuse and exploitation.

They reportedly operate under the “kafala” system, where a foreign domestic worker’s legal status is tied to their employer. This means that the workers cannot shift jobs or leave the country without permission.

This system has sparked widespread abuses on migrants from confiscation of passports, unpaid wages and excessive work hours, to beatings and sometimes rape by male members of the household.

“These young women go there with big hopes of changing their lives, but they end up suffering,” Hussein Khalid, the executive director of HAKI Africa, a Kenyan charity that supports migrant workers in the Gulf said.

“They are tortured and trapped by their employers. In some cases, they are deported or they return in coffins,” Khalid said.

Over 100,000 Kenyan workers work in Saudi Arabia, in a bid to escape joblessness at home and eyeing huge returns from work. These workers send millions of dollars back home annually, according to data by the government and central bank.

In 2020 alone, remittances from the Gulf nation hit over $120 million – up 50 per cent from 2019.

Fished from poor households in little-known-of towns and villages, local agencies recruit domestic workers and offer them two-year contracts with a monthly wage of about 25,000 Kenyan Shillings ($220)– slightly over three times what they would earn in Kenya.

For a number of women, it appears like a golden opportunity to amass money to purchase land, build a house, set up a business and even send money home.

DREAMS CUT SHORT

In some cases, however, distraught calls and cries for help begin within weeks of arriving in Saudi Arabia.

Those who manage to escape abuse from their employer’s households are rarely documented and a new risk befalls them. They could soon be exploited by traffickers who sell them into other abusive homes or even for sex.

Right groups say that the migrants when found by police face charges for absconding and are often held for months before deportation.

In 2020, there were 1,025 cases of Kenyans in distress compared to 883 in 2019, according to the foreign ministry, but family members said workers’ cries for help often go unheeded.

“My sister was being tortured there. She sent messages about how she was scared and that her boss was trying to kill her just days before she died,” Stephen Oluoch, whose sister Caroline died in the Arab nation in April, says.

“When you call the agent, they’re rude. The embassy in Riyadh doesn’t even respond to messages or say they will follow-up but never do. If someone had listened, her death could have been prevented.”

Oluoch detailed that Caroline, a 24-year-old second-year university student from the western town of Homa Bay, took up a job as a maid in Saudi Arabia last November to earn money in a bid to complete her degree and become a teacher.

In less that six months after arrival, her naked body was found covered in a sheet in the bathroom of a psychiatric hospital.

According to Saudi police, she died by hanging and declared the cause of death as suicide, but her family strongly believes he was murdered.

They revealed that she was forcefully admitted to the hospital by her employer after an attempt to flee.

‘OUR APOLOGIES’

In September, a senior Kenyan foreign ministry authority raised an issue with the increasing deaths in a parliamentary committee.

“It’s not possible that these young people are all dying of cardiac arrest,” Principal Secretary Macharia Kamau said, adding that no follow-up probe into the deaths had been conducted by Kenyan authorities.

Presently, the foreign ministry, the families and social activists want a temporary ban on domestic workers going to Saudi Arabia.

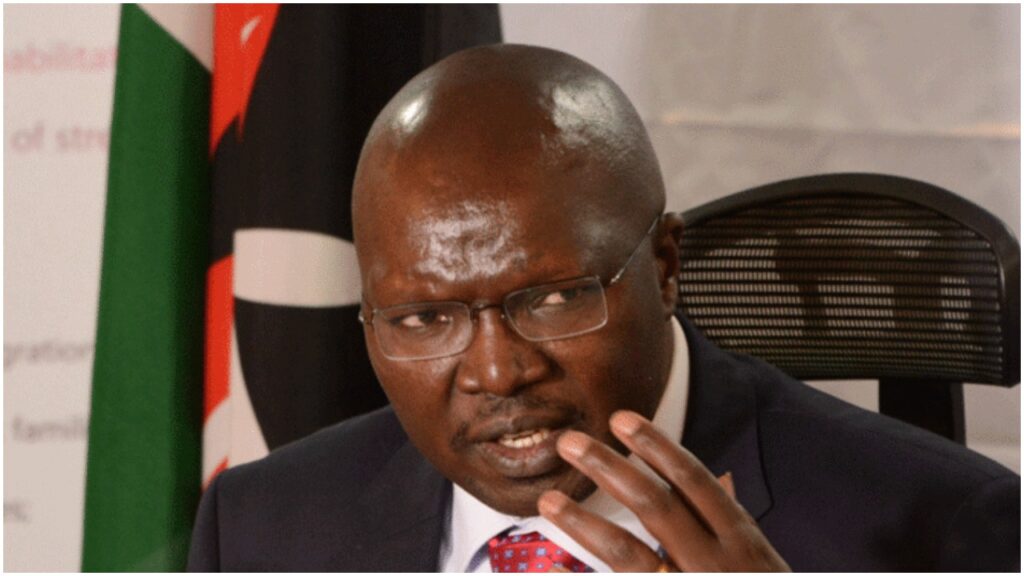

However, Peter Tum, the principal secretary at the labour ministry, says bans do not work.

Between 2014 and 2018, Kenya halted workers going to the Gulf following abuses, but the move led to more illegal migration and cases of mistreatment, he said, adding that unlicensed recruitment agencies were often to blame for violations.

“We are sorry as a government that these things are happening,” Tum told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“We really feel for the families that have lost their loved ones in this kind of manner … this is something that has absolutely disturbed us,” he said.

The government is taking a series of measures to “once and for all” end abuses against Kenyan workers, and will review Nairobi’s existing agreement with Riyadh to better protect those in Saudi Arabia, Tum said.

“A government delegation is expected to visit Saudi Arabia before the end of the year, and plans to raise concerns over the causes of the deaths of Kenyan workers,” he added.

The ministry is also stepping up vetting of hiring agencies, recalling the licences of those with unethical practices and working to raise awareness in rural areas.

More labour attaches will be appointed at the embassy in Riyadh to improve assistance, Tum added.

Meanwhile, John Awor Tindo says he just wants answers. “Even now, I’ve been asking myself ‘how could this have happened?’,” he said.

“It is very painful that your child has gone there for work, and then her body is brought back to you dead. If I knew what really happened to her, maybe I would finally be at ease.”

Recent Comments