Avellon Williams

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO- A day in history, February 11, 1990, the South African government under President Frederik Willem de Klerk released African National Congress (ANC) leader Nelson Mandela from South African prison after serving 27 years.

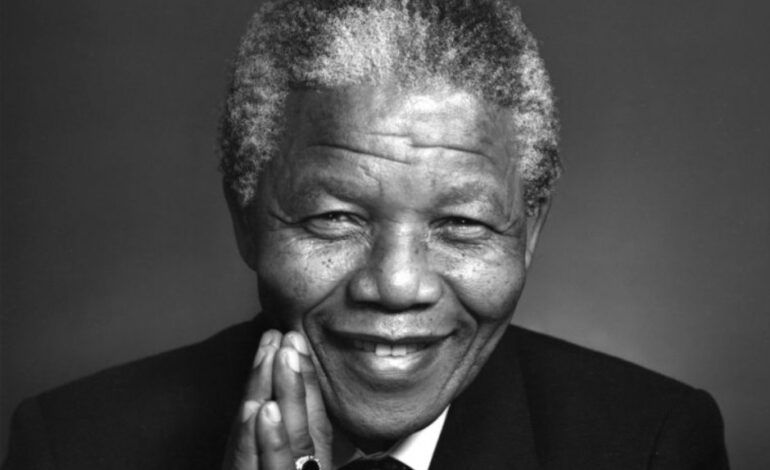

Known as Madiba, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was the first Black president of South Africa (1994-99) and a black nationalist.

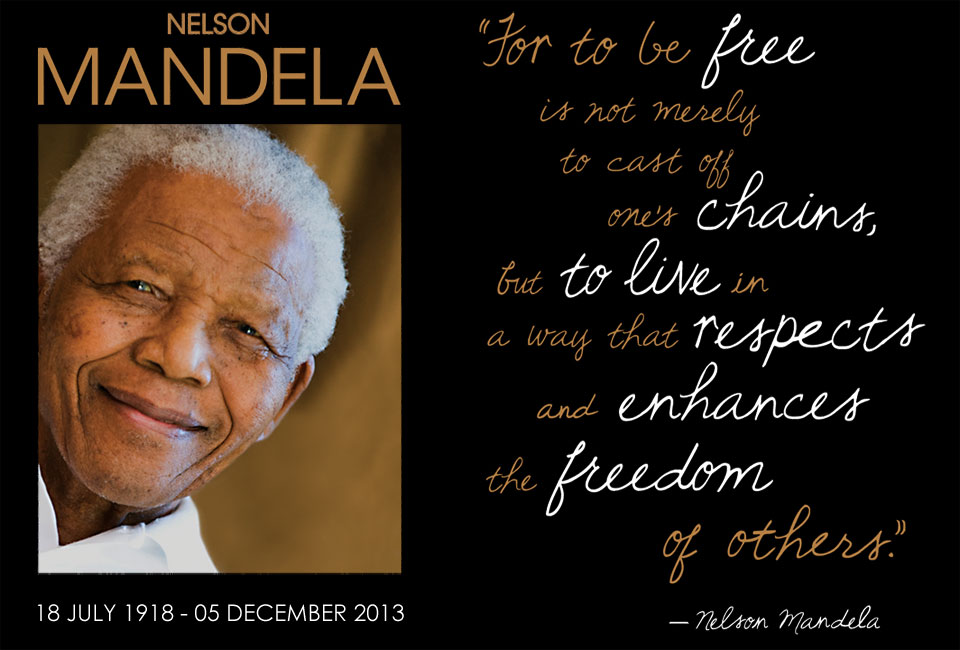

He was born in Mvezo, South Africa, on July 18, 1918, and died in Johannesburg on December 5, 2013. In the early 1990s, his negotiations with South African President FW de Klerk helped end the country’s apartheid system of racial segregation and lead to a peaceful transition to majority rule. Mandela and de Klerk were jointly awarded the Noble Peace Prize for their efforts in 1993.

EARLY LIFE AND WORK

Mandela was the son of Chief Henry Mandela, a member of the Madiba clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. In the wake of his father’s death, Nelson was raised by his regent, Jongintaba, who was a member of the Tembu tribe. Despite his claim to the chieftainship, Nelson renounced it to become a lawyer.

He was a student at South African Native College (later known as the University of Fort Hare) and as a law student at the University of the Witwatersrand, he later passed the qualification exam to become a lawyer.

It was in 1944 that he joined the African National Congress (ANC), a Black liberation group, and became part of its Youth League. In the same year, he met and married Evelyn Ntoko Mase.

Mandela went on to hold other ANC leadership positions, through which he helped revive the organization and oppose the Apartheid policies of the ruling National Party.

Mandela established South Africa’s first Black law practice in Johannesburg with ANC leader Oliver Tambo in 1952, to deal with cases arising out of the apartheid legislation following 1948.

Mandela was also an important figure in the campaign of defiance that year against South Africa’s pass laws, which required non-whites to carry official documents (called passes, passbooks, or reference books) authorizing their presence in areas deemed by the government “restricted” (i.e., generally reserved for the white population).

As part of the campaign, he traveled throughout the country to build support for non-violent protest against the discriminatory laws. During the 1950s, he contributed to the draft of the South African Freedom Charter, a document urging nonracial social democracy.

As a result of Mandela’s anti-apartheid activism, he was often targeted by the authorities. His freedom of movement, association, and speech was severely restricted (beginning in 1952). He was arrested in December 1956 with more than a hundred other people on treason charges intended to harass anti-apartheid activists.

The same year, Mandela went on trial. He was acquitted in 1961. In the extended court proceedings, he divorced his first wife and married Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela (Winnie Madikizela-Mandela).

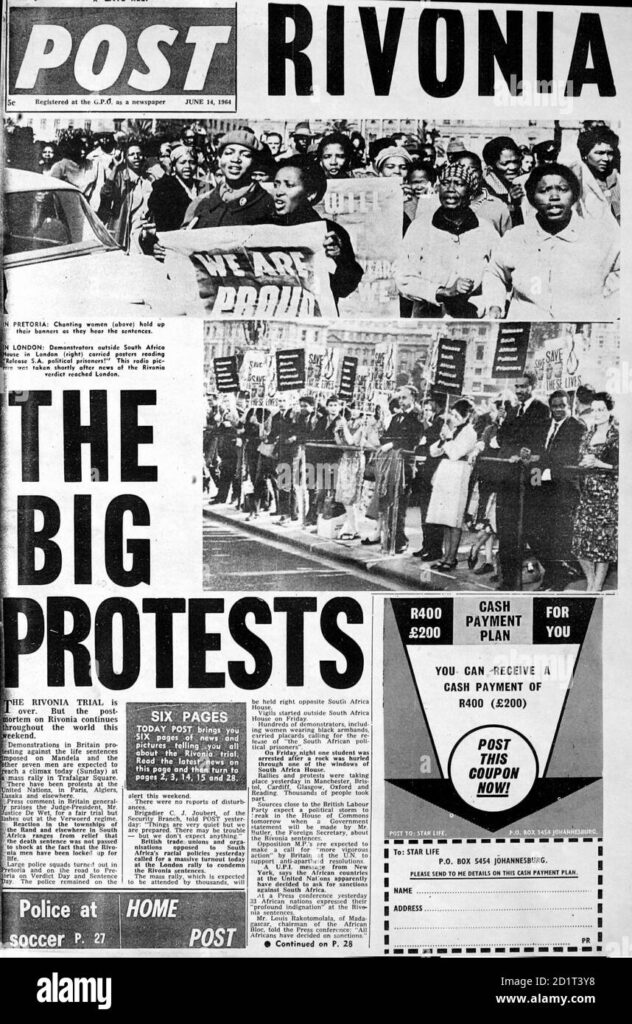

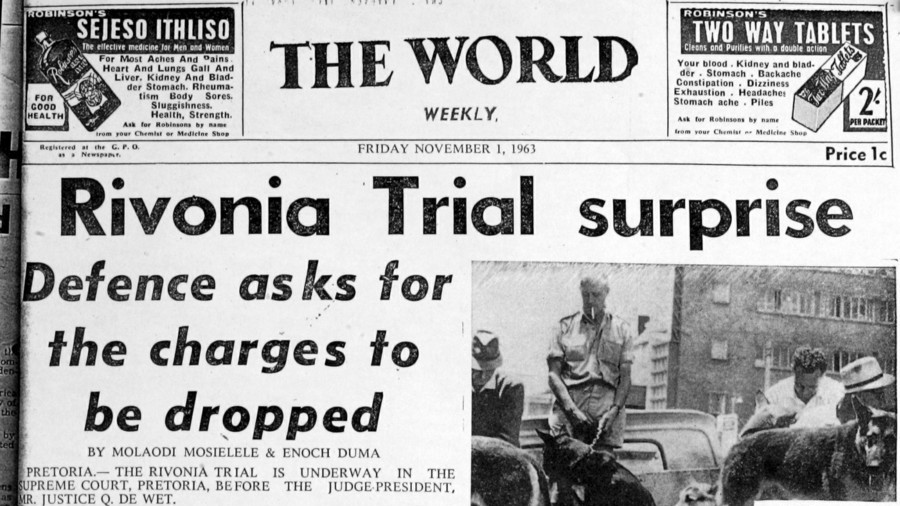

UNDERGROUND ACTIVITY AND THE RIVONIA TRIAL

In the wake of the 1960 massacre of unarmed Black South Africans by police at Sharpeville and South Africa’s subsequent banning of the ANC, Mandela abandoned his nonviolent stance and began advocating sabotage against the South African regime.

As a result of his ability to elude capture, he gained the nickname Black Pimpernel and is considered one of the founders of Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the ANC’s military wing.

After training in guerrilla warfare and sabotage in Algeria in 1962, he returned to South Africa later that year. Mandela was arrested at a roadblock in Natal shortly after his return; he was sentenced to five years in prison on August 5.

INCARCERATION

A long period of Mandela’s life was spent on Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town, from 1964 to 1982. His next stop was the maximum-security Pollsmoor Prison, where he was held until 1988, when, after being treated for tuberculosis, he was sent to the Victor Verster Prison near Paarl.

Nelson Mandela was periodically offered conditional freedom by the South African government, most notably in 1976, on the condition that he recognize the newly independent, and highly controversial, status of the Transkei Bantustan and agree to reside there. His 1985 offer included renunciation of violence.

He rejected both offers on the grounds that only free men could participate in such negotiations, and he was not a free man.

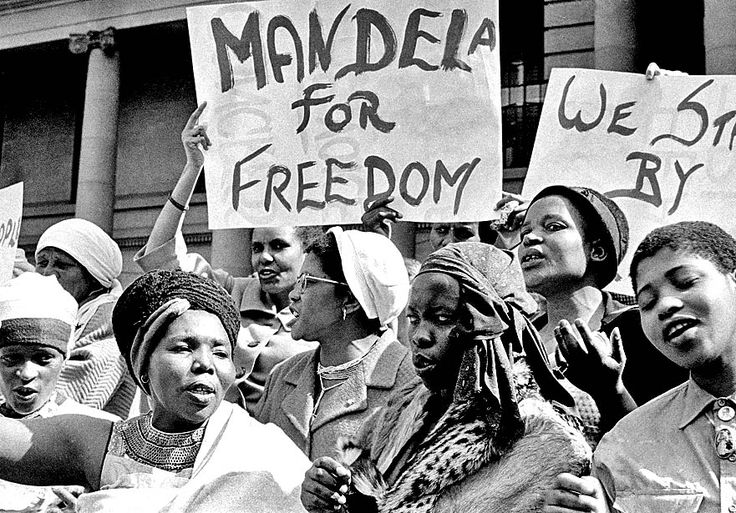

As Mandela remained imprisoned, he maintained broad support among South Africa’s Black population, and his imprisonment became a cause célèbre among international groups that condemned apartheid.

During the deterioration of South Africa’s political situation after 1983, and particularly after 1988, he was enlisted by ministers of President P.W. Botha’s government to discuss exploratory negotiations; he also met With Botha’s successor, Frederik de Klerk, in December 1989.

Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, by the government of South Africa under President de Klerk. Soon after his release, Mandela was appointed deputy president of the ANC; he became its president in July 1991.

In negotiations with President de Klerk, Mandela led the ANC to end apartheid and bring about a peaceful transition to nonracial democracy in South Africa.

PRESIDENCY AND RETIREMENT

A Mandela-led ANC won the country’s first elections by universal suffrage in April 1994, and on May 10 Mandela was inaugurated as the country’s first multiethnic president. In 1995, he established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which investigated human rights violations under apartheid.

He also introduced housing, education, and economic development initiatives aimed at improving the living standards of Blacks. A new democratic constitution was enacted under his watch in 1996. In December 1997, Mandela resigned from the ANC and the leadership of the party was transferred to Thabo Mbeki, his appointed successor.

Mandela and Madikizela-Mandela divorced in 1996, and in 1998 Mandela married Graca Machel, the widow of Samora Machel, the former Mozambican president and leader of Frelimo.

Nelson Mandela did not seek a second term as president of South Africa. He was succeeded by Thabo Mbeki in 1999. Following his retirement from active politics, Mandela maintained an international presence as an advocate of peace, reconciliation, and social justice, often through the Nelson Mandela Foundation, which he established in 1999.

He was a founding member of the Elders, a group of international leaders created in 2007 to promote conflict resolution and problem-solving across the globe. In 2008 Mandela was feted with several celebrations in South Africa, Great Britain, and other countries in honour of his 90th birthday.

In honor of Mandela’s legacy, Mandela Day is observed on Mandela’s birthday, which promotes service around the world.

On July 18, 2009, Nelson Mandela International Day was first observed, and it was sponsored primarily by the Nelson Mandela Foundation and 46664 (the foundation’s HIV/AIDS global awareness and prevention campaign); subsequently, the United Nations proclaimed the day to be observed annually.

Nelson Mandela’s writings and speeches were compiled in I Am Prepared to Die (1964; updated ed. 1986), No Easy Walk to Freedom (1965; updated ed. 2002), The Struggle Is My Life (1978; updated ed. 1990), and In His Own Words (2003).

His autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, chronicling his early years in prison, was published in 1994. The unfinished draft of his second memoir was completed by Mandla Langa and published posthumously as Dare Not Linger: The Presidential Years (2017).

THE MEMORY OF NELSON MANDELA WILL NEVER DIE

Nelson Mandela will always be remembered as one of the most influential people in South Africa’s history who led his people out of darkness and into the light fighting for freedom, equality, justice, and human rights.

Recent Comments