Thandisizwe Mgudlwa, Cape Town, SA

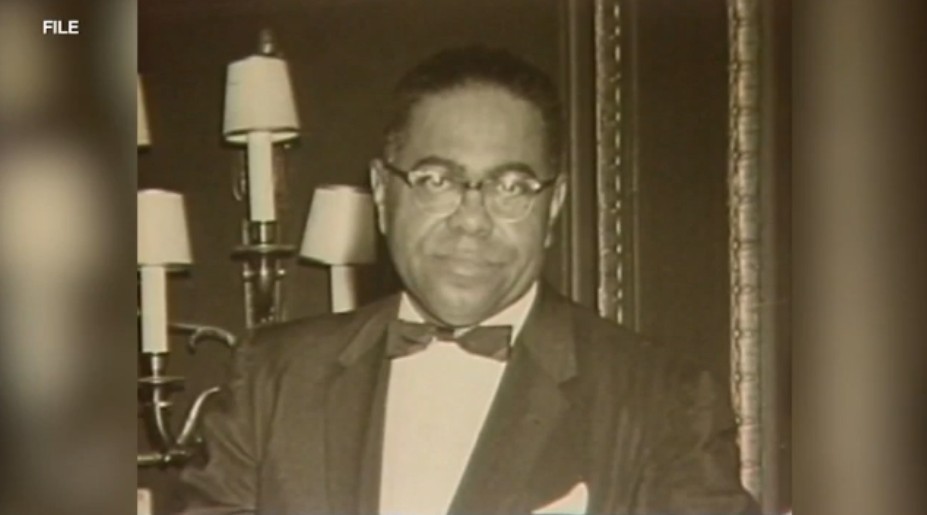

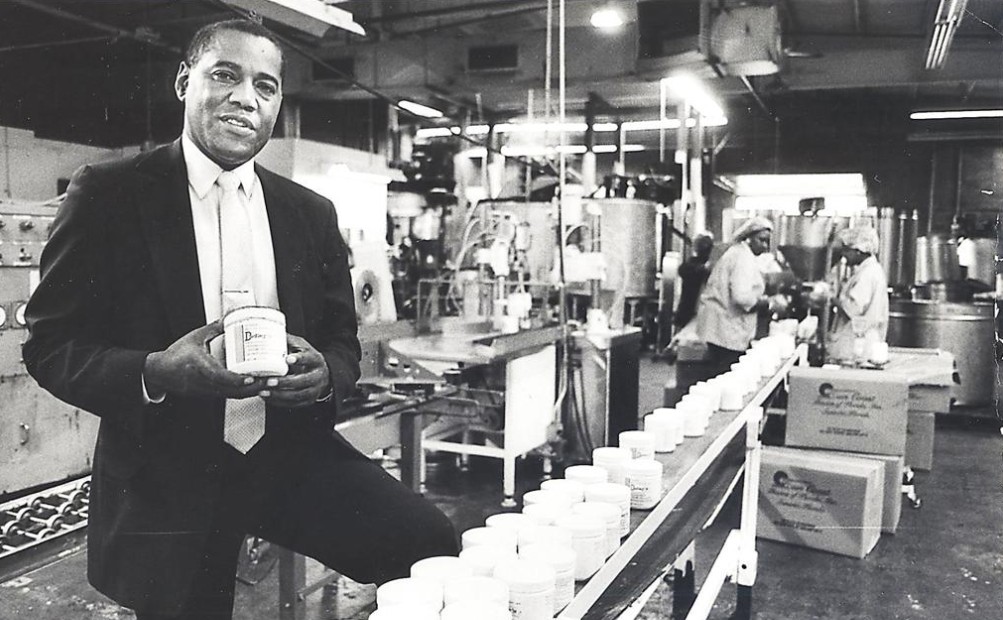

From poverty to glory is perhaps how the story of Samuel Fuller could be best described. But is was not an easy journey by far. In-fact, it was a long hard road for S.B. Fuller before he could even begin to assemble the wildly successful business that would become Fuller Products Company.

The son of Louisiana sharecroppers, his family was so poor that he was forced to drop out of school in the sixth grade to help on the farm. When he was only seventeen years old, in 1922, Fuller’s mother passed away, and he was called into action to use his budding talent as an entrepreneur to support his other six siblings.

As a young man, he was able to make the leap and move to Chicago, Illinois in 1928, only a year before the Great Depression hit.

If Fuller was going to make a business success of himself, he would have to do so through the poverty and calamity of the Depression.

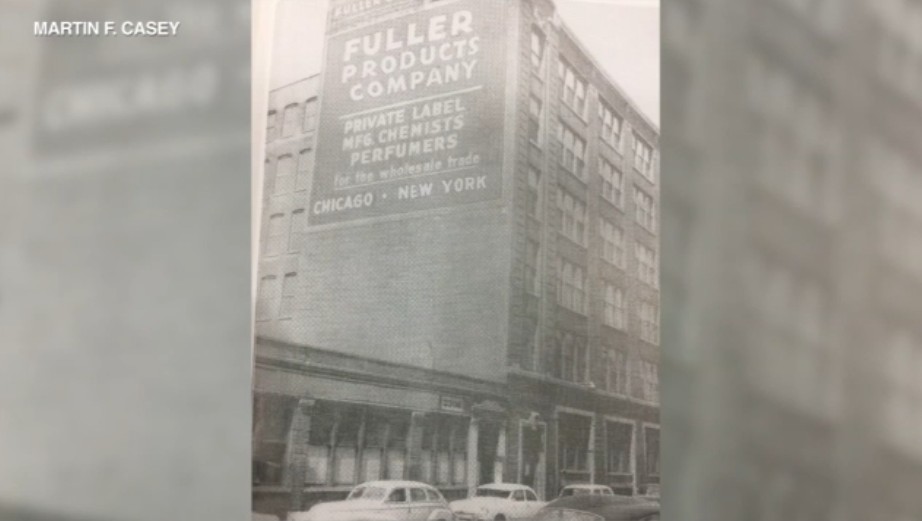

But make a success he did. As Fuller founded his own company, Fuller Products, in 1929, and stuck through it while simultaneously working another job as an insurance rep. In 1939, after ten years of toil, he was able to build Fuller Products its own factory.

And by the 1950s, Fuller was bringing in over $10million in sales each year. He was founder and president of the Fuller Products Company, publisher of the New York Age and Pittsburgh Courier, head of the South Side Chicago NAACP, president of the National Negro Business League, and a prominent Black Republican.

S. B. Fuller’s life was an illustration of business success and self-help. His company gave inspiration and training to countless aspiring entrepreneurs and future leaders, including John H. Johnson of Johnson Publishing, George Ellis Johnson founder of Johnson Products, and Dr.T. R. M. Howard.

Joe L. Dudley Senior of Greensboro, North Carolina had a similar business, the Dudley Products Company, which was a major distributor of Fuller products and also offered products of its own and kept the Fuller Products name alive after the end of S. B. Fuller’s career.

George Johnson, later a business mogul in his own right as founder of Johnson Products Company, spent ten years of his early career learning under the mentorship of Samuel Fuller.

Mr Johnson recalled, “What Mr. Fuller was doing in 1944 was taking people off of welfare and making them independent. People were leaving welfare, in a short time, buying homes or getting into better apartments, buying cars. It was a amazing what Mr. Fuller was doing with people, people who were just not going anywhere. He gave them a focus. He inspired them, and he told them where to look to find the inspiration.”

George Johnson

In an interview (U.S. News World Report – August 19, 1963 ) he spoke of this time ” …the relief people came and offered us some relief, but we did not accept it because it was a shame in those days for people to receive relief. We did not want our neighbors to think we couldn’t make for ourselves. So we youngsters made it for ourselves.”

After going to Chicago in 1928, Fuller worked in a wide range of menial jobs, eventually rising to become manager of a coal yard. Subsequent to his employment in the coal yard, he gained employment as an insurance representative for Commonwealth Burial Association, an African-American firm. Although he had a secure job during the Depression, he nevertheless struck out on his own preferring “freedom” to “security.”

Fuller’s career as an entrepreneur started after he borrowed twenty-five dollars using his car as collateral. Along with his friend Lestine Thornton (who later became his wife), he invested in a load of soap from Boyer International Laboratories, manufacturer of Jean Nadal Cosmetics and HA Hair Arranger.

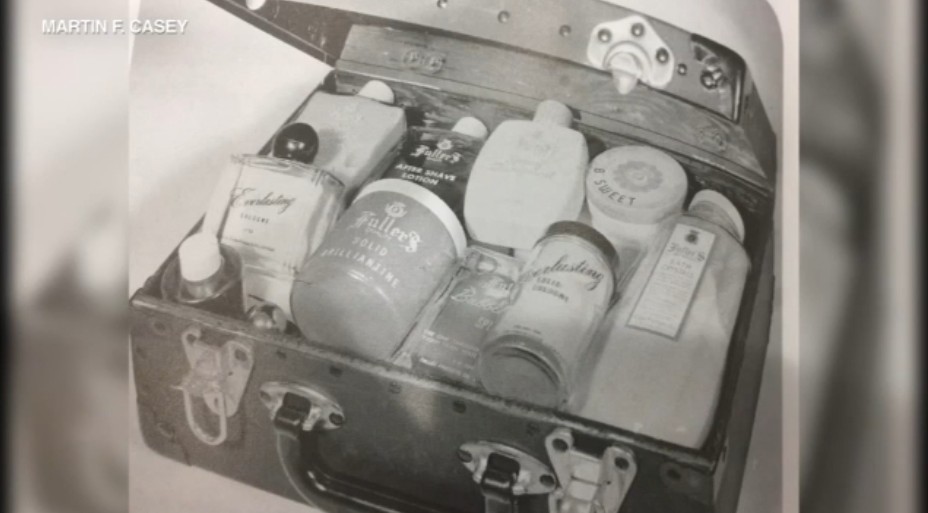

His success selling soap door-to-door inspired him to invest another $1000. He incorporated Fuller Products in 1929. In four years he would be promoted to a manager at Commonwealth while continuing to grow his own company to a line of 30 products and hiring additional door-to-door salespeople.

The substantial number of African American families who moved to the South side of Chicago during The Great Migration [ also known as – Great Northward Migration or Black Migration of 6 million Blacks from the rural south to North America suburbs ] became the customer base from which Fuller Products would see tremendous expansion.

The additional growth was sufficient for the company to open its own factory in 1939. In 1947, Fuller purchased Boyer to prevent its bankruptcy, keeping his ownership a secret.

The company began to manufacture and sell a diverse line of commodities from deodorant and hair care to hosiery and men’s suits. Fuller also purchased several newspapers including the New York Age and the Pittsburgh Courier.

Additionally, he owned the South Center Department Store and the REGAL THEATER in Chicago. Fuller was a leading Black Republican although he always had an independent streak. He promoted civil rights and briefly headed the Chicago South Side NAACP.

Along with Birmingham businessman, A. G.Gaston, he tried to organize a cooperative effort to purchase the segregated bus company during the Montgomery bus boycott. He told Martin Luther King Jr., “The bus company is losing money and willing to sell. We should buy it.” King was skeptical of the idea, and not enough African American people came forward to raise the money. And despite his belief in civil rights, Fuller’s emphasis was always on the need for African American people to go into business.

In 1958, he blasted the federal government for undermining free enterprise and fostering socialism. He feared that it was “doing the same thing today as was done in the days of Caesar— destroying incentive and initiative.

“He argued that wherever “there is capitalism there is freedom. “Fuller was a good friend and associate of Dr. T. R. M. Howard, of Mound Bayou, Mississippi and later Chicago. Howard was a wealthy black entrepreneur and a prominent civil rights leader and mentor to Medgar Evers.

Fuller and Howard had probably met because of their mutual involvement in the National Negro Business League. Fuller was president of the organization for several terms in the 1940s and 1950s. He hired Howard to be medical director of Fuller Products and supported his Republican campaign for Congress in 1958.

And during the 1950s, Fuller was probably the richest African American man in the United States. His cosmetics company had $18 million in sales and a sales force of five thousand (one-third of them white).

It gave training to many future entrepreneurs and other leaders. “It doesn’t make any difference,” he declared, “about the color of an individual’s skin. No one cares whether a cow is black, red, yellow, or brown. They want to know how much milk it can produce.”

Despite his opinion, the White Citizens Councils organized a boycott of Fuller’s Nadal products line during the 1950s, when they learned an African American owned the company. This would be the beginning of a turn of fortune for Fuller’s business interests that would affect his activities throughout the 1960s.

In 1963 Fuller was the first African American inducted into the National Association of Manufacturers. During his acceptance speech he stated that “a lack of understanding of the capitalist system and not racial barriers was keeping blacks from making progress.” In an interview that same year with U.S. News & World Report he said, “Negroes are not discriminated against because of the color of their skin. They are discriminated against because they have not anything to offer that people want to buy.”

Afterwards his company suffered severe setbacks as many of his comments were reported out of context. Major national black leaders reacted angrily and called for a boycott of Fuller Products. In 1968, Fuller sold unregistered promissory notes in interstate commerce for which he was charged with violating the Federal Securities Act.

After pleading guilty, being placed on five years’ probation, and ordered to repay creditors $1.6 million, Fuller Products entered bankruptcy in 1971. Although the company reorganized, and reported profits of $300,000 in 1972, and the cosmetics portion of the old company was rebuilt, it never returned to the firm’s previous levels of size or profitability.

And in 1976, Fuller, as a result of health problems, asked his top distributor, Joe Louis Dudley, Sr., to move to Chicago and become President of the Fuller Products Company. Dudley ran both Fuller Products Company and Dudley Products Company from 1976 until 1984. In1984, Fuller Products Company was purchased by Dudley.

Fuller is the father-in-law of neurologist and Canadian football hall-of-famer Tom Casey. Fuller was 83 years of age when he died at St. Francis Hospital in Blue Island, Illinois from kidney failure.

Long may his legacy live!