Faith Nyasuguta

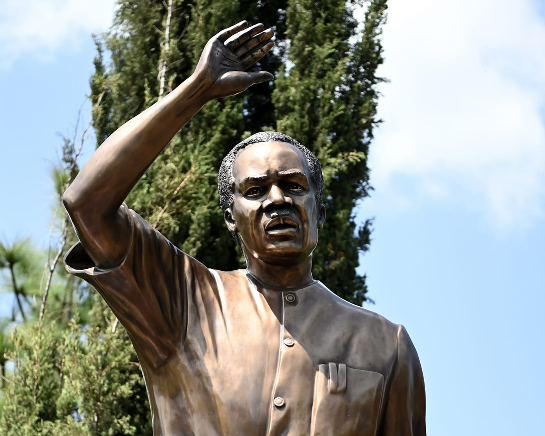

French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop’s (pictured) documentary film, “Dahomey,” premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, chronicles a historic event—the return of 26 looted treasures from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris to the royal palace of the kingdom of Dahomey in modern-day Benin.

This momentous act of restitution, announced by French President Emmanuel Macron three years prior, marked the first major return of looted treasures from Europe to Africa in the 21st century.

However, the film sheds light on the complex emotions and nuanced perspectives surrounding this restitution, particularly the feelings of humiliation expressed by the people of Benin.

The documentary captures the joyous celebrations in Cotonou, Benin’s economic capital, as the returned artifacts were paraded from the airport to the presidency.

Towering wooden thrones and lifesize zoomorphic statues, among other treasures, were met with enthusiasm. However, the film doesn’t shy away from the underlying discontent and critical discussions among the younger generation.

Students in the film express dissatisfaction, deeming the restitution of 26 works out of an estimated 7,000 still held in European museums as insufficient, with one student bluntly stating, “Restituting 26 works out of 7,000 is an insult.”

Mati Diop, known for her acclaimed feature debut “Atlantics,” provides a nuanced perspective on the restitution process. The filmmaker emphasizes the need for broader participation beyond political agendas, suggesting collaboration with artists, filmmakers, and students to shape the narrative.

While acknowledging the positive step taken with the return of the artifacts, Diop underscores the lingering challenges and complexities surrounding restitution efforts.

Musée du Quai Branly, France’s largest ethnological museum, holds 3,157 other objects from Benin in its collection. More are believed to reside in smaller museums and private collections.

The artefacts already returned, which include a towering wooden throne and lifesize zoomorphic statues, were paraded from Cotonou airport to the presidency in trucks bearing large photographs of the objects.

“We need to think about how this process was staged,” Diop said. “There’s a political agenda certainly, but also there are other ways to respond, with artists, filmmakers, students.”

The film prompts a reflection on the imbalance between the returned items and those that remain in European collections.

Originally conceived as a fiction film due to Diop’s skepticism about the immediate physical transfer of the treasures, “Dahomey” captures a historic moment that unfolded sooner than anticipated.

The film becomes a platform for dialogue, inviting viewers to consider the staged nature of the restitution process and advocating for a more inclusive and culturally sensitive approach to address the broader issue of looted artifacts.

Despite the positive momentum, the film highlights the ongoing challenges, with efforts to restore more colonial-era objects to Benin facing hurdles in the French parliament.

“Dahomey” stands as a testament to the complexities and multifaceted nature of the restitution of cultural heritage to its rightful origins.

RELATED: