Avellon Williams

PORT-AU-PRINCE- During the Haitian Revolution, slaves, colonists, the British and French armies, and others fought it out between 1791 and 1804 in an effort to establish independence from slave trade.

With the aid of the struggle, Haiti’s people eventually gained independence from France and thereby became the first country founded by former slaves.

SLAVERY AND COLONIALISM

Spanish enslavement of the indigenous Taino and Ciboney people began soon after December 1492. Christopher Columbus sighted the island he called La Isla Espanola (“The Spanish Island”; was later Anglicized as Hispaniola).

By the end of the 16th century, the island’s indigenous population had almost disappeared. European diseases and harsh working conditions had devastated the island’s indigenous population. The island was stricken with slaves imported from other Caribbean islands.

Spanish settlements were abandoned after the main gold mines were exhausted, and the French established their own settlements, including one in the northwest called Port de Paix (1665), under the control of the French West Indies Corporation.

In the late 17th century, landowners on western Hispaniola imported increasing numbers of African slaves. On the eve of the French Revolution in 1789, Saint-Domingue, as the French called their colony, had an estimated population of 556,000 with roughly 500,000 slaves from Africa, 32,000 European colonists, and 24,000 affranchis (free mulattos [people of mixed African and European descent] or blacks).

Throughout Haitian history, human society has been deeply divided by race, class, and gender. Some of the affranchis, most of whom were mulattoes, were slave owners themselves and aspired to the same economic and social levels as the Europeans.

Despite the fear of and disdain for the slave majority, the white European colonists of the time, who included merchants, landowners, overseers, craftsmen, and the like, generally discriminated against them. With the colony’s struggle for independence, affranchis’ aspirations played a major role. Most slaves were African-born, including people from various West African groups.

The vast majority of them worked in the fields; others were household servants, boilermen (at sugar mills), and even slave drivers. Long workdays and backbreaking labor led to slaves dying of injuries, infections, and tropical diseases. Slaves also suffered from malnutrition and starvation.

A few slaves managed to escape into the mountainous interior, where they became known as Maroons and waged guerrilla warfare against the colonial militia.

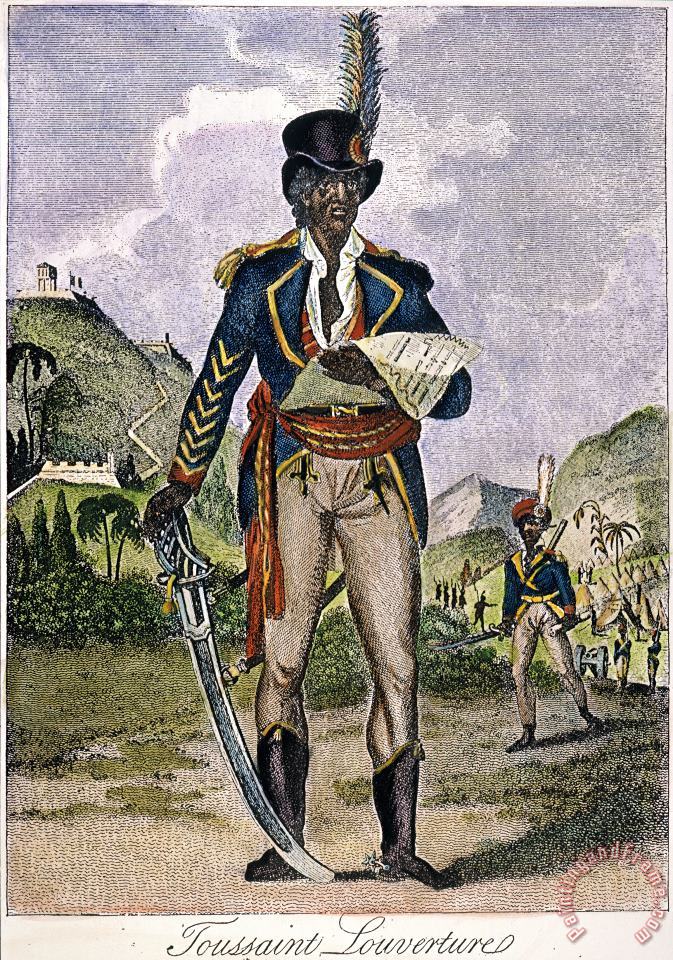

CONFLICT AND THE EMERGENCE OF TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE

An era of revolutionary conflict arose from this background in the early 1790s. The conflicts were sparked by the affranchis’ frustration with a racist society, the French Revolution’s turmoil in the colony, nationalistic rhetoric used in Vodou ceremonies, the brutality of slave owners, and ongoing wars between European powers. In late 1790, mulatto leader Vincent Ogé led an uprising against the Parisian assembly for colonial reforms but was captured, tortured, and killed.

In May 1791, the French revolutionary government granted citizenship to the wealthier affranchis, but Haiti’s European population did not follow the law. A few months later, Europeans and affranchis fought, and in August thousands of slaves revolted. In order to quell the slave revolt, Europeans appeased the mulattoes.

In April 1792, the French assembly granted citizenship to all affranchis. As a result, the country was torn apart by rival factions, some of which were supported by Spanish colonists in Santo Domingo (on the eastern side of the island, later known as the Dominican Republic) or by British troops from Jamaica.

As early as 1793, a French commissioner appointed to maintain order, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, offered freedom to slaves who joined his army; within a year, he eliminated slavery altogether, a decision ratified the following year by the French government.

Throughout the late 1790s, Toussaint Louverture, a former slave and military leader, gained control over several regions and gained the support of French agents. His nominal allegiance to France did not prevent him from pursuing his own political and military ambitions, which included negotiating with the British.

Toussaint conquered Santo Domingo in January 1801 and in May of that year appointed himself “governor-general for life”. He decreed military rule on the island, returned the peasants to work on the plantations, and induced many property owners to return.

In December 1801, Napoléon Bonaparte (later Napoleon I), in an effort to maintain control over the island, sent his brother-in-law, Gen. Charles Leclerc, in command of an experienced force from Saint-Domingue that included Alexandre Sabès Pétion and several other exiled mulatto officers.

Toussaint fought Leclerc’s forces for several months before agreeing to an armistice in May 1802; however, the French violated the agreement and imprisoned him in France. Toussaint died on April 7, 1803.

THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF HAITI

As early as 1802 some of Toussaint’s lieutenants—most notably Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe—returned to the fight against the French. Mulatto leaders such as Pétion and others joined them in their anger at the restoration of caste restrictions.

Mulattoes and blacks were enraged by reports that France had reestablished slavery in Guadeloupe and Martinique, and their struggle was fought with great desperation.

A yellow fever epidemic weakened the French. Leclerc died in November 1802 from the disease. Likewise, in May 1803 Napoleon’s withdrawal from North America was announced with the Louisiana Purchase. Less than three weeks later, the French position in Haiti became truly hopeless when hostilities were renewed between France and Britain on May 18, 1803.

Under the leadership of Dessalines, the Armée indigène eventually defeated the French at the Battle of Vertières on November 18, and Gen. Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur surrendered Cap-Français (now Cap-Haitien), the last significant French fortification. In accordance with the surrender terms, the French had ten days to evacuate, but Rochambeau took his time embarking on his troops.

In response, Dessalines threatened to fire his cannon on the French ships at anchor in the harbour of Cap-Français. Interestingly, it would take the Royal Navy, which had been blockading Saint-Domingue since the resumption of the Napoleonic Wars, to carry out the evacuation.

John Bligh, commanding officer of the British Navy, treated Rochambeau and Dessalines, and in the end, the French garrison was forced to leave Cap-Français as prisoners of the British. While French military action on Haiti came to an end with this event, France continued to maintain a presence on the island’s eastern shore until 1809.

Under the Arawak-derived name of Haiti, the entire island of Haiti became independent on January 1, 1804. During the slave revolt, many European powers and their Caribbean allies ostracized Haiti, fearing the spread of slave revolts, while the United States reacted in different ways.

Slave-owning states tried to suppress news of the rebellion, but merchants in the free states wanted to trade with Haiti rather than European powers. Almost the entire population was utterly destitute as a consequence of slavery, which has left a profound mark on Haitian history.

Dessalines was crowned Emperor Jacques I in October 1804, but he was killed trying to suppress a mulatto revolt in October 1806; Henry Christophe then assumed control of the territory from his capital in the north. A civil war ensued between Christophe and Sabès Pétion, based in Port-au-Prince in the south.

In 1811, Christopher, who declared himself King Henry I, improved the country’s economy but at the cost of making former slaves work on plantations again. A spectacle of a palace (Sans Souci) as well as an imposing fortress, La CitadelleLaferrière, were built in the hills south of the city Cap-Haitien, where mutinous soldiers almost made their way to his door in 1820, so he committed suicide.

After Haiti declared its independence in 1825, France only recognized the country with a hefty indemnity of 100 million francs and a repayment period of until 1887.

RELATED

Recent Comments