Faith Nyasuguta

If architects are indeed individuals who relish navigating challenges, then constructing schools in Burkina Faso presents an ideal scenario.

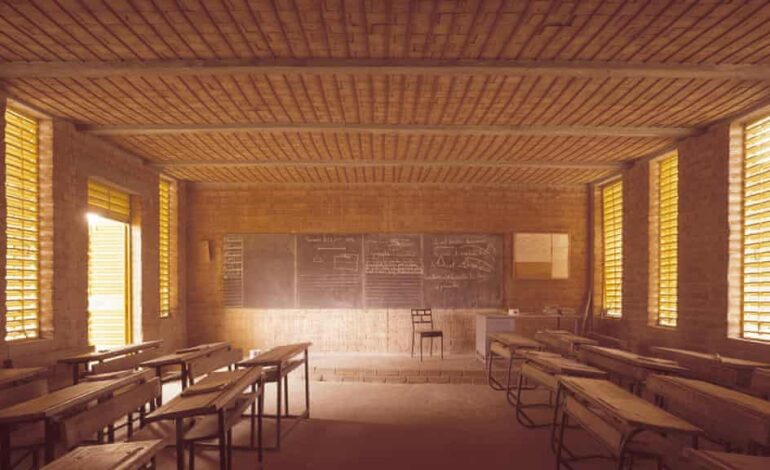

The myriad challenges include sweltering temperatures during high seasons, constrained resources, scarcity of materials, electricity, and water, and a client base composed of vulnerable and youthful individuals. The puzzle to solve: how to create a cool and inviting environment under the relentless African sun, especially when air conditioning isn’t an option?

Architect Diébédo Francis Kéré, hailing from the small village of Gando, intimately understands these challenges. Collaborating with other architects, such as Albert Faus, they employ resourceful methods utilizing affordable materials to ensure that the schools and orphanages they erect across Burkina Faso are not only structurally sound but also offer a cool haven.

Kéré, the recipient of the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2022, fondly reflects on the support he received as a child from his community. Their collective contributions enabled him to pursue education, leading him eventually to secure a scholarship for studies in Germany. “The reason I do what I do is my community,” he asserts.

The Gando primary school, a testament to Kéré’s ingenuity, was constructed in 2001 after he completed his studies. Initially met with skepticism from the community about building with local clay rather than opting for glass structures common in Germany, Kéré had to persuade them of the benefits of using indigenous materials.

Men and women collaborated in the construction, merging traditional techniques like clay floors, hand-beaten to a smooth finish, with modern technology for enhanced comfort.

Another significant project in Kéré’s portfolio is the Noomdo orphanage. Pierre Sanou, a social educator at the orphanage, notes, “The Kéré building provides us with good thermal comfort because when it’s hot, we’re cool, and when it’s cold, we’re warm inside.” This, he adds, eliminates the need for air conditioning, resulting in remarkable energy savings, crucial in a region where temperatures can reach 40°C (104°F) during the hottest season.

Sanou emphasizes Kéré’s strategic use of local materials like laterite stone and minimal concrete. Kéré’s buildings prioritize permeability, facilitating the natural flow of air while offering protection from the sun.

Eduardo González, a member of the Architecture School of Madrid, highlights Kéré’s innovative adaptation of the ancient concept of raised and extended metal roofs. A metal plate, positioned above the concrete beam, not only shields the roof from direct sunlight and rain but also allows the release of accumulated hot air. This technique, reminiscent of vernacular architecture in the Persian Gulf, is seamlessly integrated into Kéré’s contemporary designs.

Privacy and security considerations for vulnerable users, primarily minors living in the Noomdo orphanage, are integral to the semicircular design. Boys’ dormitories on one side and girls’ on the other, with administration acting as a bridge between them, ensure a balanced layout. Sanou describes three visibility zones within the building, maintaining the privacy of the children without resorting to fences or barbed wire.

In a nearby village called Youlou, architect Albert Faus designed the Bangre Veenem school complex, employing similarly inventive methods to cool the structure. Ousmane Soura, an education adviser at the school, recounts Faus’s pre-construction efforts, involving consultations with traditional authorities to respect sacred spaces.

The comprehensive school complex, accommodating nursery to high school, including a professional school, has successfully created an environment where students remain comfortable and focused.

The school, constructed with bricks made from native laterite stone, boasts intense red hues and enhanced durability. Soura notes, “They are more resistant to bullets than concrete blocks, which have two holes in the centre.”

Faus’s commitment to minimizing material transportation and utilizing locally sourced materials, including employing quarry workers from the area, contributes to the overall beauty and acceptance of the structures by local communities.

Burkina Faso, ranking 184th out of 191 countries in the Human Development Index, faces significant challenges, including limited access to electricity for only 22.5% of its population as of late 2020.

Soura emphasizes the positive impact of these architectural innovations, allowing students to study and charge their phones at night, thanks to solar panels providing light. The improved learning environment fosters better concentration and, subsequently, improved results.

Ultimately, architects like Diébédo Francis Kéré and Albert Faus are not merely constructing buildings; they are weaving narratives of community support, sustainability, and innovation in a challenging context. Their designs not only tackle the immediate architectural needs but also contribute to the broader goals of education, empowerment, and environmental responsibility in Burkina Faso.

RELATED: