Avellon Williams

PORT-AU-PRINCE, HAITI – “I’m not living in a good country.” Nadia swaddles the crying 3-month-old baby and kisses her gently on the forehead while holding her.

The 19-year-old was not ready to become a mother. Last year, while walking home from class on the dusty streets of a gang-controlled part of Haiti’s capital, the young Haitian’s life changed.

Blindfolded and kidnapped, she was dragged into a car by a group of men. She was beaten, starved, and gang-raped for three days.

Several months later, she learned that she was pregnant. Suddenly, her dreams of studying and economically improving her family were shattered.

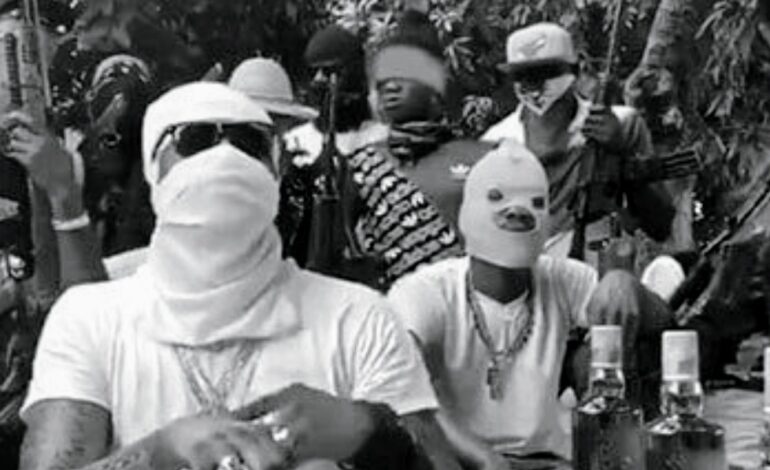

In the midst of Haiti’s crisis-stricken Caribbean nation’s ongoing gang violence, the toxic slate of gangs are increasingly weaponizing women’s bodies in their war to control the country. The consequences are felt by women like Nadia.

“The most difficult part is that I have nothing to give her,” Nadia said of her daughter. “I’m scared because as she gets older to ask about her father, I won’t know what to tell her. … But I will have to explain to her that I was raped.”

Nadia

In an interview with AP, which does not identify sexual violence survivors, the woman only offered the name Nadia, which is not her real name.

Having suffered natural disasters, political turmoil, poverty, and waves of cholera, Haiti spiraled into chaos after the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in 2021.

A barbaric way of sowing terror in communities and asserting control, sexual violence has long been used as an instrument of war across the globe.

Renata Segura, deputy director for Latin America and the Caribbean for International Crisis Group said, “they’re running out of tools to control people.”

“They extort, but there’s only so much money that can be extorted from people that are really poor. This is the one thing they have they can inflict on the population.”

Port-au-Prince has been shaken by that fear. The fear of kidnapping and rape by gangs discourages parents from sending their children to school. Even at night, the bustling streets of the city are deserted.

Going outside the house poses a risk to women in particular. The threat of rape is also used by gangs to keep communities from leaving their control areas.

The U.N. special envoy to Haiti, Helen La Lime, told the Security Council in late January that gangs use sexual violence to “destroy social fabric,” particularly in rival gang-controlled areas.

It is reported that girls and boys as young as 10 are raped. The damage is further compounded by underreporting, making it difficult for authorities to grasp the full scope of the problem. There is a fear that gangs will seek revenge on them, and women are just as trusting of Haitian police as they are of gangs.

There has been no comment from the country’s current government on how it plans to deal with the problem, which many views as illegitimate.

In 2022, the U.N. documented 2,645 cases of sexual violence, an increase of 45% over the previous year. In reality, those numbers are just a fraction of what there are in terms of assaults. There were several people who didn’t report, including Nadia.

Upon learning she was pregnant, she debated whether to keep the baby, but decided to give her daughter the best life possible. Having been born in Port-au-Prince, a place with a high level of poverty, it became impossible for the new mother to work or study. However, doctors such as Jovania Michel are trying to fill in the gaps.

In Port-au-Prince, Michel works in the epicenter of gang warfare, Cite Soleil. Among those she encounters are mothers who were gang-raped after their husbands died; sexual violence survivors living on the streets, fearing it might happen again; and sexually transmitted infection survivors.

“Sexual violence is a way to paralyze, to scare people. The minute there’s an increase in sexual violence, everyone stops moving, people don’t go to work because they’re scared,” Michel said. “It’s a weapon, it’s a way to send a message.”

One 36-year-old woman spoke with the AP dressed in a shirt with bright red roses, her hair carefully braided. Her name has been withheld out of fear of retaliation. To put her daughters and son through school, she and her husband ran a boutique in the capital of Haiti. They were confronted by armed men in July, members of the gang G-Pep, asking for money to buy bullets.

( / AP)

As the men could not get the cash, they took her husband away at 8 p.m. She discovered his body the next day in a gutter. In order to escape the neighborhood, she sent her children to live with relatives and friends elsewhere in the city. During this time, she slept alone on the streets, joining at least 155,000 other Haitians forced to flee their homes. She was raped and beaten by the gangsters in December when she tried to return home.

“I’m a professional, and out of nowhere these bandits come … and made me lose everything. I’m not good. I’m not okay. It all makes me really angry. I got to a point that I wanted to kill myself,” the woman said. Keeping a firm jaw and tilting her head upward, she brushed away tears. In an attempt to report the rape to the police, they told her they did not handle gang cases.

The only thing that gives her hope today, while sleeping in a park with other forcibly displaced Haitians, is that her children might still have a better future. It worries her what deep instability and a rising gang control in Haiti will mean for the country. “I’m not living in a good country,” she said.