Avellon Williams

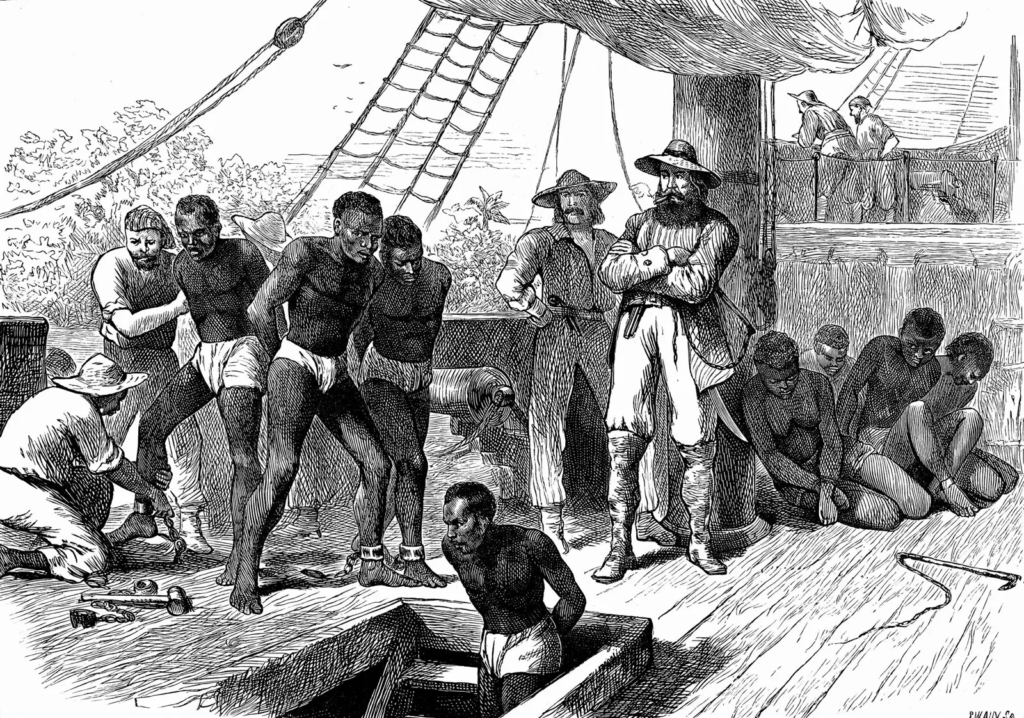

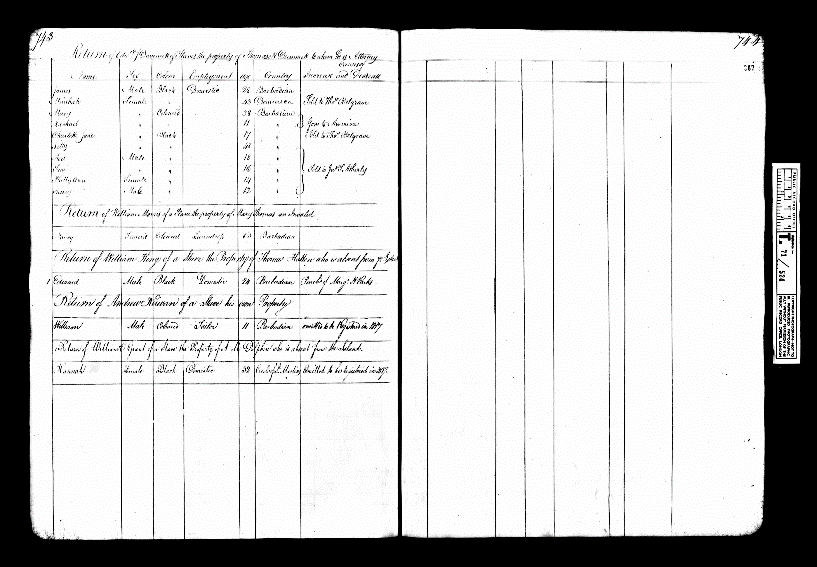

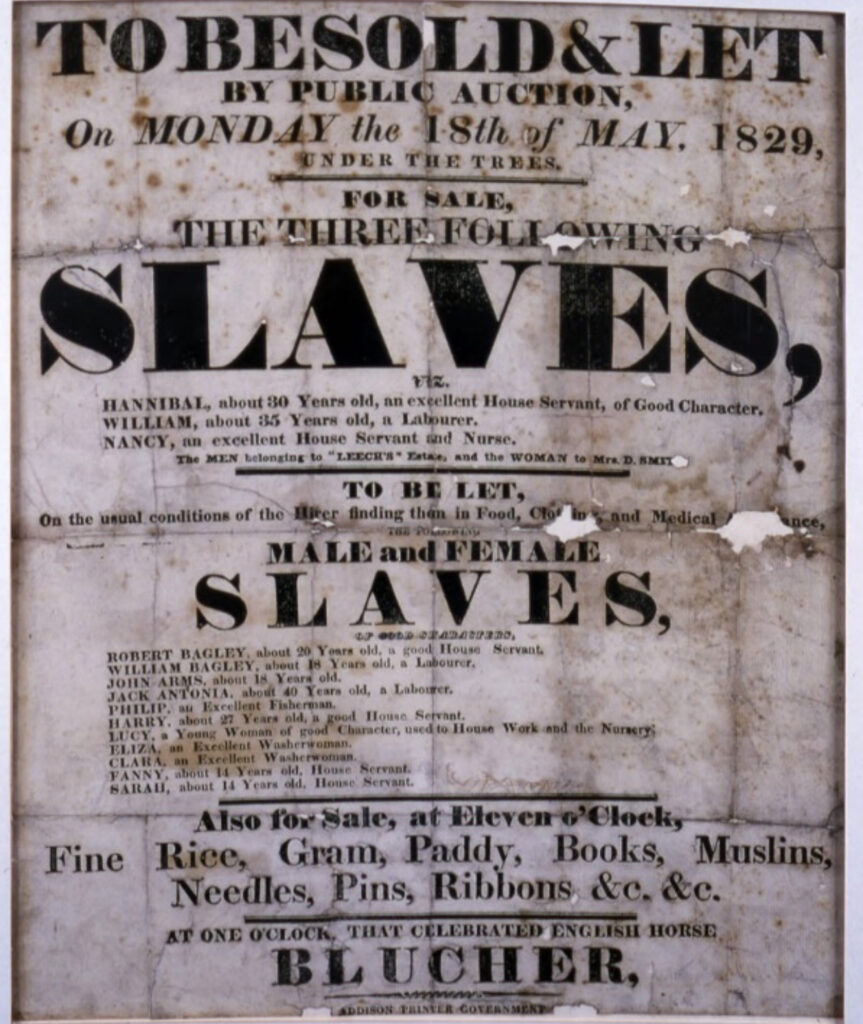

ST. LUCIA- As early as 1807, the British abolished the Slave Trade and proclaimed that no country should trade enslaved persons from Africa illegally. Despite this, the trade continued. Thus, slave registers became a means of tracking and destroying the illegal slave trade by recording the names of the enslaved. Two colonies, St. Lucia and Trinidad, started slaves’ registers in 1814.

A few discrepancies exist in the slave registers. In St. Lucia, most of the enslaved registers were in French [but this is the problem]. According to Barry Higman, the local officials complained that slaveholders had been submitting reports very late and that some of the information had been repeated. The 1815 Slave Registers, for example, contained 80 percent of the 1,024 slaves’ returns submitted by December.

In addition, 13% of 1815 slaves’ returns were recorded by January 1816. There can be no concrete definite statistics for the enslaved population from slave registers. Slave registers are, however, an excellent source for distinguishing between plantation slaves and island slaves.

Furthermore, slave registers provide information on the enclave’s age and slave owner, which is useful for understanding them. Higman suggests that some of the problems with slave registers are associated with small urban slaveholders. Therefore, their slave return reports contained many repetitions.

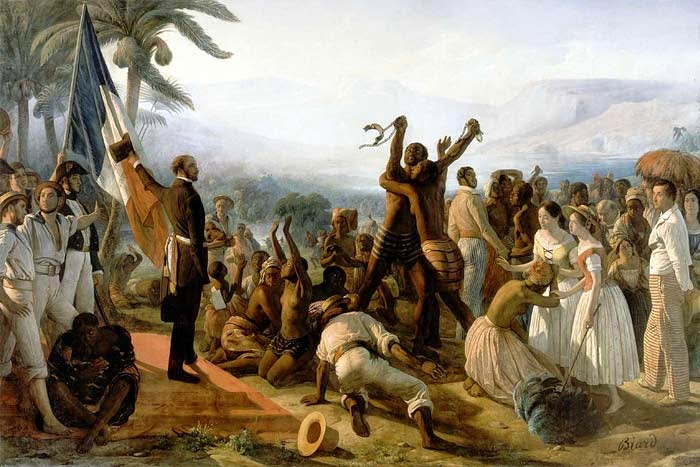

ORIGIN OF THE ENSLAVED PEOPLE

Due to the island’s mix of French and English slaveholders, the enslaved population of St. Lucia originated from various locations in West Africa. From 1600 to 1700, Senegambia was the home of a substantial number of enslaved people, according to Jolie Harmsen.

In contrast, when St. Lucia became a British colony, many of the enslaved were of Akan and Eastern Nigerian descent. Harmsen adds that “Neg June (Guinea Africans) were likely to be of Ewe/Fon origin and Neg Kongo of Congo/Angolan origin.”

Enslaved people throughout the region were both Creoles and Africans. According to the Slave Registers of Former British Colonial Dependencies for St. Lucia, there is no category for Origin of the Enslaved, but there is a section titled Nationality, which serves the same purpose.

It would be, for instance, the case of Mary Anah, a 37-year-old female whose nationality was Congolese, or the case of Fanny Collins, a 24-year-old female whose nationality was Dominican. In the Registers, it is evident that the enslaved population in St. Lucia came from different ethnic groups.

RITUALS

1. BAPTISM

Because of the differences between French and English practices regarding slave baptism and marriage, the enslaved population on the island had a very peculiar baptismal and marriage system. It was the Roman Catholic faith that was practiced among the French, while the Protestant faith was practiced among the English. In terms of enslaved baptism, the churches take distinctly different approaches.

In Richard Hart’s opinion, Catholic priests were more involved in the lives of enslaved people than Protestant priests. Due to this, the priests in the French Caribbean became part of the enslaved lives. In terms of moral issues, the Protestants believed that the enslaved had direct access to God. In addition, Sir Frederick Thomas explains that the French King mandated by law that the enslaved were full converts of the Catholic faith, so baptism and other sacraments like marriage were highly encouraged.

When the island came under British control in 1815, some of its British customs were enforced. The enslaved were treated as “pieces of property by law and were excluded from church sacraments“, as Parry and Sherlock wrote.

The French Catholic religious laws allowed the enslaved to express their identity through the church, despite the inhumanity of slavery in both the British and French West Indies. There was a good relationship between the French enslaved and the clergy, which facilitated the dissemination of the Catholic doctrine.

2. NAMES

Names given to enslaved people reflected their character or the lack of interest of slaveholders in finding suitable names. According to Barry Higman, enslaved people’s surnames displayed on slave registers were simply given to satisfy colonial office requirements.

On the Choc Plantation, the enslaved were given surnames of the year in French, such as Janvier, Fevrier, Mars, and Avril. Also, the enslaved on Voletwere given surnames derived from drinks or liquids such as syrup, limes, rum, Sangree, Grog, Brandy, Gin, Champaign, Madeira, and Porter.

In addition, Margot Thomas points out that some enslaved acquired their names based on an extremely noticeable physical characteristic or a link to their behavior. As one example, Frederic Tharel’s enslaved named Coffy Gros-Yeux – which means large eyes and John McCall’s enslaved named Andrew Barker for being quarrelsome. Margot Thomas also explains how some masters named their slaves.

Higman acknowledges in his text Slave Populations of the British Caribbean 1807-1834 that he did not attempt to explain the cultural significance of slave surnames. There can be no doubt that Higman is correct when he states that “naming practices can be expected to provide insight into the functioning of slave communities.”

Names of enslaved people were given by planters and not by their parents. Even though the Creole enslaved had biological parents, the planters and other slaveholders arguably usurped many of their traditional parenting duties.

Enslaved people had their names given as a way of seasoning themselves. Africans were given new names by the planters to purge them of their roots, according to James Walvin, new names, the enslaved acquired a new identity. Having a new name suggests that the masters wanted the enslaved to forget about their old homes because their names define who they are and reveal theirbackground.

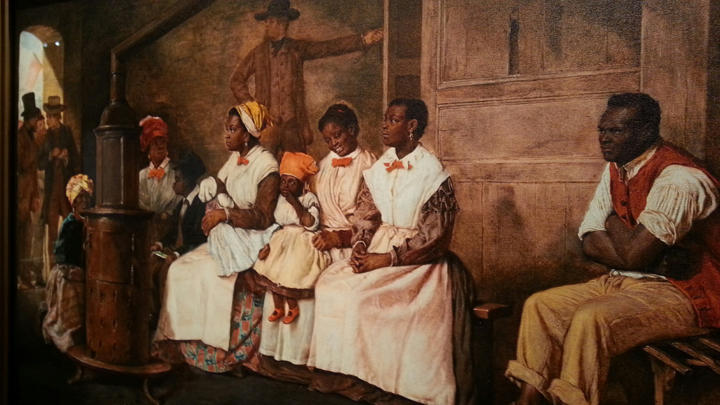

3. MARRIAGE

Marriage is another aspect of enslaved life that tells us more about the communities of enslaved people in St. Lucia. As a result, there appears to have been a prohibition on weddings, as couples were encouraged to cohabitate by the many British owners.

It can be argued that slaveholders prohibited enslaved people from becoming married to reinforce their premise that the slaves were property. Furthermore, slaveholders, especially planters, encouraged their enslaved to cohabit for reproductive purposes.

The following report from William Burnley stated that there had been an increase in marriages among the freemen in St. Lucia four years after the apprenticeship period ended. Moreover, Burnley mentioned that most marriages were between old couples who had cohabited for a long time.

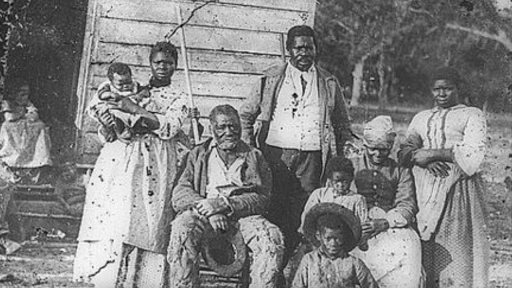

Enslaved people living in rural areas were also more likely to live as families than those living in urban areas, Engerman and Higman assert. As an example, in 1815, “69% of rural slaves were accounted for by families, compared to 55% of town slaves.” The slaveholder reared the children reproduced by the enslaved women in urban areas.

As the Creole population grew, kinship grew, especially since “cross-population mating became common.” A cohabiting couple’s children became legitimate right away when they married, and if the parents died without a will, the children would be entitled to their parents’ properties.

4. WAKES

For different occasions, such as festivals and death, enslaved communities had many traditions and practices. A community in Saint Lucia – such as Babonneau – practices rituals in the wake of its dead family that originated with the traditions of enslaved people, according to Malena Kuss.

As part of the practice kele, wakes were held from the night an enslaved died until the interment. On each night of the wake, sympathizers kept the bereaved family company until daybreak. A chantwöle would be conducted, in which other people repeated the lines or joined in the singing.

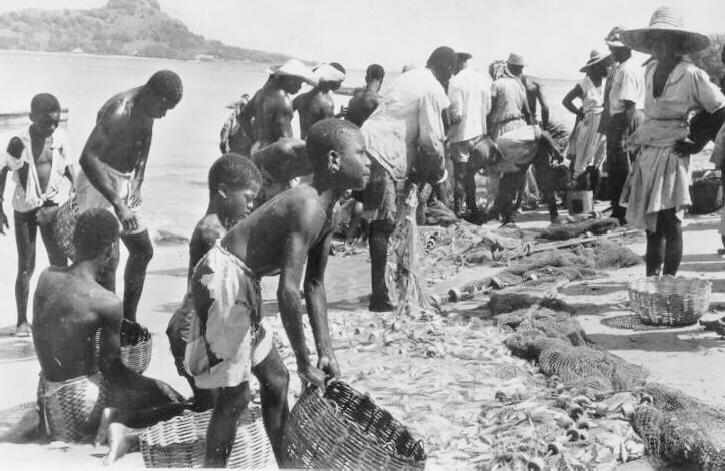

5.FESTIVALS

A cultural village on the Guinea Coast Neg Jine, Piaye is home to hundreds of communities using drums and dance forms passed down from their ancestors. Their oral tradition preserves the history of the African enslaved through songs and folklore. According to Auguste, the Rose and La Marguerite celebrations illustrate how the enslaved mimicked the French-English rivalry. In addition, it depicted the bitter relationship between enslaved people and slave owners. Besides dances, there were folklores describing stories or events that occurred in Africa – Anansi’s stories, Ti Jean’s stories, etc.

6. AGE

It is not known what the ages of the enslaved population were according to the Personal and Plantations Slave Registers. Under the Age category, the word about appears before an enslavedbirth year. The Personal Slaves Register 1815, for example, lists Thomas Bea as an enslaved of Jean Fcois Rechou born about 1806; his age was recorded as nine (9). According to Higman, slaveholders estimated the age of enslaved by observing their physical appearance.

Furthermore, Higman explains that in 1815, in the urban areas of St. Lucia – specifically Castries – there were more enslaved women in their twenties than on the plantations. Since slaveholders’ economic activity was predominantly in urban areas, it was common to have younger enslaved women.

Among the enslaved women were prostitutes, washerwomen, nannies, and wet nurses. As with sex and birthplace, the age determined whether an individual was an urban or rural enslaved. Consequently, many of the younger enslaved women lived in urban areas to satisfy the main economic activity on the island, which was very different from rural life. Comparatively to their female counterparts, the majority of male enslaved worked on cotton, coffee, and sugar plantations.

7. FOOD

Enslaved people in rural and urban areas were fed meager diets. Rural planters were required by law to provide half an acre of land to each enslaved person. Because of the land provision, the planters had the freedom to provide fewer food allowances to the enslaved. Urban enslaved depended solely on their slaveholders for their food and money allowances.

A very small allowance was given to the enslaved if the slaveholders were poor. Higman explains that if there were droughts in rural areas, the price of food in urban areas would be high. As a result, enslaved people receiving cash allowances sometimes were unable to purchase food. Scavenging and theft increased in urban areas due to a lack of food.

8. HOUSING AND ACCOMMODATION

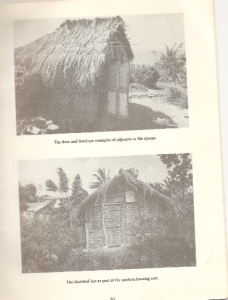

St. Lucia’s enslaved lived in Ajoupas, which Higman describes as “well thatched, wattled, plastered, and whitewashed.” According to Joyce Auguste, many of the enslaved families had two or more ajoupas as living, kitchen,and sleeping quarters – there was also a thatch-covered pit latrine.

Depending on the system, enslaved people lived in rectangular compartments with a unit for each member of the family. To keep out the rain, these houses were made of local timber and imported nails, with shingles covering the roofs and outer walls.

According to Higman, enslaved people built their own houses on given plots of land. In general, the size and quality of the drivers and skilled tradesmen were considerably better. Slaves in the urban areas lived in slaveholders’ backyards called ‘masters’ negro yards’, while domestic workers lived on their properties.

There were some cases when urban enslaved slept with their masters or mistresses or occupied rooms near the kitchen or storeroom of their masters or mistresses. As a precaution against fires, Higman states that the houses of the urban enslaved were later built out of stone or brick.

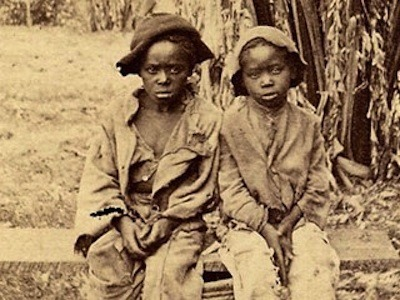

9. CLOTHING

In rural areas, enslaved people wore ‘miserable’ clothing, not because it was poor in quality but because there were so few items available. During that time, the men wore coarse linen breeches and headwear. Even though women didn’t have head coverings, they wore skirts. Stockings and shoes were not worn by men or women; children up to the age of four to five remained naked. As early as age five, they wore linen robes, and by the age of ten, the boys were dressed as fathers and the girls as mothers.

Additionally, Higman explains that by the 19th century most planters were giving the enslaved the materials to make their clothes since the law required slaveholders to provide the meager garments to their slaves.

As a form of punishment, the planters would withhold clothes from their workers. As a result of the scarcity of clothes, enslaved people slept in the same clothes even when it was raining. Slavery clothes for urban enslaved people consisted mainly of cast-offs from slaveholders. In this way, the clothing of enslaved people was determined by the slaveholder’s wealth. Plantation men wore flocks, but urban men wore waistcoats. It was more common for urban slaves to wear shoes than rural slaves.

10. LANGUAGE

Albert Valdman believes that French Creole originated in St. Kitts, the first settled colony in the Caribbean. Following that, it spread to Martinique, Guiana, and Guadeloupe, and the language spread to St. Lucia via Martinique thanks to the early enslaved islanders who came from Martinique. Before St. Lucia was seized by the British, Martinique and St. Lucia were under the same government.

Approximately 95 percent of St. Lucia’s enslaved came from Martinique. To remove the African culture from the enslaved population, the French planters taught them, French, according to John Jeremie.

As a result, the enslaved retained part of their African language and combined it with French to create the language known as kwéyol. Henry Breen describes the language as unintelligible and jargon-filled, so the letter “r” became obsolete, and the word “ki” and “ka” became the roots of past tenses.